Audrey is an older woman living in a tent in rural Redding, California. She is hypoglycemic and hasn’t had a glucose test in years. Now she is suffering from a medical condition that is common among elderly women – incontinence. Unlike other women, Audrey doesn’t have the resources to prevent accidents and wakes up soaked in urine every morning. She doesn’t have the money to clean up her tent, her clothes, or her blankets. It’s already difficult living out your senior years as homeless; people shouldn’t suffer like this, without access to medical attention. Homelessness in California has been on the rise for the last several years, leading to an increased need for medical attention for those experiencing homelessness. Thankfully, organizations like Shasta Community Health Center are meeting that need with their HOPE Program and its Medical Director, Dr. Kyle Patton. Through this program, street medicine is being used to bring medical attention directly to people where they are—on the streets. Homelessness can be a harrowing experience that leaves people vulnerable and without access to basic healthcare. Street Medicine is an innovative approach to providing medical care in unconventional places, like the woods and under bridges, where homeless individuals have no other options. In this four-part series, Brett Feldman, Director of Keck Street Medicine at the University of Southern California, introduces us to four Street Medicine programs that deliver healthcare in the woods, under the bridges, behind dumpsters, and wherever else people who are experiencing homelessness are living. Today, join us as we join Dr. Kyle Patton in Redding, California – the most rural area of the four communities we visited. This video series is brought to you by the Invisible People and the California Health Care Foundation to augment street medicine research in California. Please visit https://chcf.org/streetmedicine for more information and to sign up for CHCF’s newsletter to be notified when the research is released. About the California Health Care Foundation The California Health Care Foundation is dedicated to advancing meaningful, measurable improvements in the way the health care delivery system provides care to the people of California, particularly those with low incomes and those whose needs are not well served by the status quo. We work to ensure that people have access to the care they need, when they need it, at a price they can afford.

More street medicine teams tackle the homeless health care crisis

Originally published on CalMatters Dec. 8, 2022

Living on the streets of California is a deadly affair. The life expectancy of an unsheltered person is 50, according to national estimates, nearly 30 years less than that of the average Californian. As homelessness spirals out of control throughout the state, so too do deaths on the street, but it’s those whose lives are the most fragile who are least likely to get medical care.

Now, the state Medi-Cal agency is endeavoring to improve health care access for people experiencing homelessness. Through a series of incentives and regulatory changes, the Health Care Services Department is encouraging Medi-Cal insurers to fund and partner with organizations that bring primary care into encampments.

They’re known as street medicine teams. There are at least 25 in California.

“Oh crap. This is where she was, and they just swept that,” said Brett Feldman on a Friday morning in November, looking at a green tent, crumpled and abandoned on Skid Row in Los Angeles. Feldman, a physician assistant, is searching for a female patient in her 40s with severe and unmanaged asthma. She cycles predictably in and out of the hospital, and Feldman knows she’s due for another hospitalization soon.

Go to the site to read more: https://calmatters.org/health/2022/12/homeless-health-care/?fbclid=IwAR3bpEwBmUMNV9jT7P1BZbgms9AV-iDxGryY5ws6UJO76ZV8SH5PaOvWMOs&fs=e&s=cl

3rd Annual LA Street Medicine Symposium

|

EVENT: |

3rd Annual LA Street Medicine Symposium |

|

DATE: |

Friday, August 20, 2021 |

|

REGISTER: |

Please click here: LA Street Medicine Symposium |

|

CONTACT: |

For questions please contact usccme@usc.edu |

Accreditation Statement

The Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical

Education (ACCME) to provide continuing medical education for physicians

Credit Designation

The Keck Medical Center of the University of Southern California designates this live Activity for a maximum of 6.25 AMA PRA

Category 1 Credits™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

The following may apply AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ for license renewal: Registered Nurses may report up to 6.25 credit hour(s) toward the CME requirements for license

renewal by their state Board of Registered Nurses (BRN). CME may be noted on the license renewal application in lieu of a BRN provider number. Physician’s Assistants:

The National Commission on Certification of Physicians’ Assistants states that AMA PRA Category 1 CreditsTM accredited courses are acceptable CME requirements for recertification.

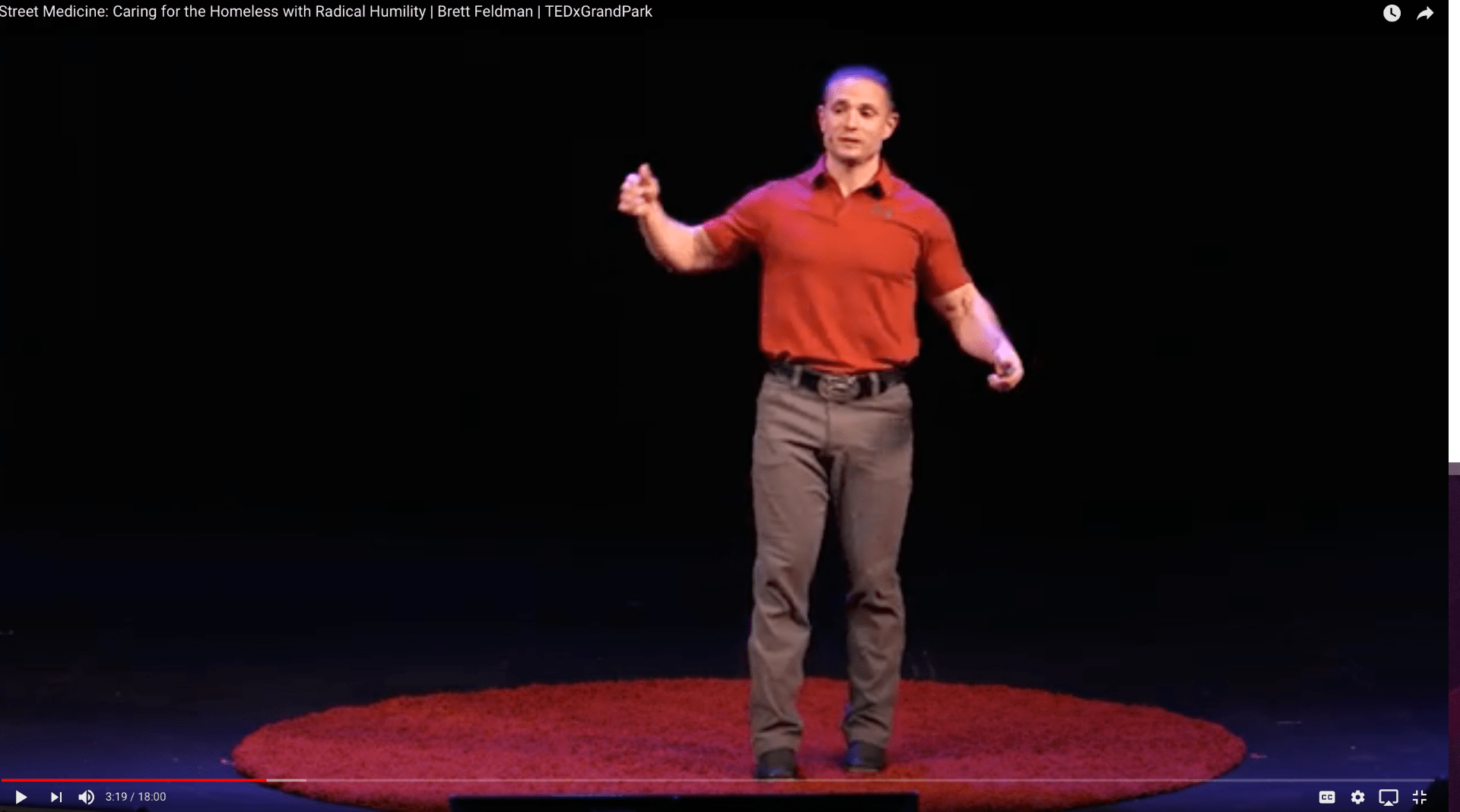

Street Medicine: Caring for the Homeless with Radical Humility | Brett Feldman | TEDxGrandPark

“Homelessness is certainly not just houselessness”. Brett Feldman reveals his radical approach to caring for our homeless neighbors as the Director of Street Medicine at USC Keck School of Medicine in Los Angeles, CA. In this talk, Brett shares his story about bringing a Street Medicine program to Los Angeles after founding and directing a successful program in Pennsylvania for over a decade. His remarkably humble, compassionate, and consistent approach to caring for patients on the streets fosters extraordinary trust and camaraderie, which in turn renders extraordinary results in patient outcomes. A PBS documentary featuring Brett and the street medicine program which he founded, Close to Home: Street Medicine, won an Emmy award in 2018. His work has been featured on the BBC, Washington Post, CNN, the Associated Press, and Telemundo. Brett J. Feldman, MSPAS, PA-C, is the Director of Street Medicine at the Keck School of Medicine (KSOM) of USC and serves as the Vice-Chair of the International Street Medicine Institute. He has practiced homeless medicine since 2007 and founded three programs including the DeSales University Free Clinic, Lehigh Valley Health Network (LVHN) Street Medicine in Allentown, PA, and the KSOM of USC Street Medicine in Los Angeles, CA. In 2017, Mr. Feldman and LVHN hosted the 13th Annual International Street Medicine Symposium in Allentown, PA. He is a winner of the Pennsylvania Society of Physician Assistants Humanitarian of the Year Award, Penn State University Alumni Service Award, and the Lehigh Valley Healthcare Hero Award. Brett J. Feldman, MSPAS, PA-C, is the Director of Street Medicine at the Keck School of Medicine (KSOM) of USC and serves as the Vice Chair of the International Street Medicine Institute. He has practiced homeless medicine since 2007 and founded three programs including the DeSales University Free Clinic, Lehigh Valley Health Network (LVHN) Street Medicine in Allentown, PA, and the KSOM of USC Street Medicine in Los Angeles, CA. In 2017, Mr. Feldman and LVHN hosted the 13th Annual International Street Medicine Symposium in Allentown, PA. He is a winner of the Pennsylvania Society of Physician Assistants Humanitarian of the Year Award, Penn State University Alumni Service Award and the Lehigh Valley Healthcare Hero Award. His work has been featured in the BBC, Washington Post, CNN, the Associated Press and Telemundo. A PBS documentary featuring Brett and the street medicine program which he founded, Close to Home: Street Medicine, won an Emmy award in 2018. This talk was given at a TEDx event using the TED conference format but independently organized by a local community. Learn more at https://www.ted.com/tedx

‘This Is the Burning Building.’ Inside One Man’s Mission to Treat LA’s Homeless for COVID-19 as seen in Esquire

Street medicine is what it sounds like: the practice of providing health care to the unsheltered homeless—people who live in the streets, in abandoned buildings, or in their cars. There are more than 44,000 unsheltered homeless people in Los Angeles alone, the most in any American city.

It’s not even close, in fact—44,000 is more than the homeless populations of the 29 next most populous cities combined.

The 44,000 tend to live in close proximity to one another.

They tend to have higher percentages of people who are immunocompromised.

And they tend to be less aware of breaking news.

They don’t generally get treated for contagious diseases.

They don’t generally have the means to maintain good health.

The 44,000 don’t generally have doctors.

Read the whole piece here: https://www.esquire.com/news-politics/a31903973/coronavirus-homeless-los-angeles-street-medicine-brett-feldman/

Los Angeles Times features USC Street Medicine

This month the USC Street Medicine team was featured in an article that was printed on the front of the California section of the Sunday Los Angeles Times.

Please read it here: http://bit.ly/LATimesUSCStreetMed

USC Street Medicine featured on BBC

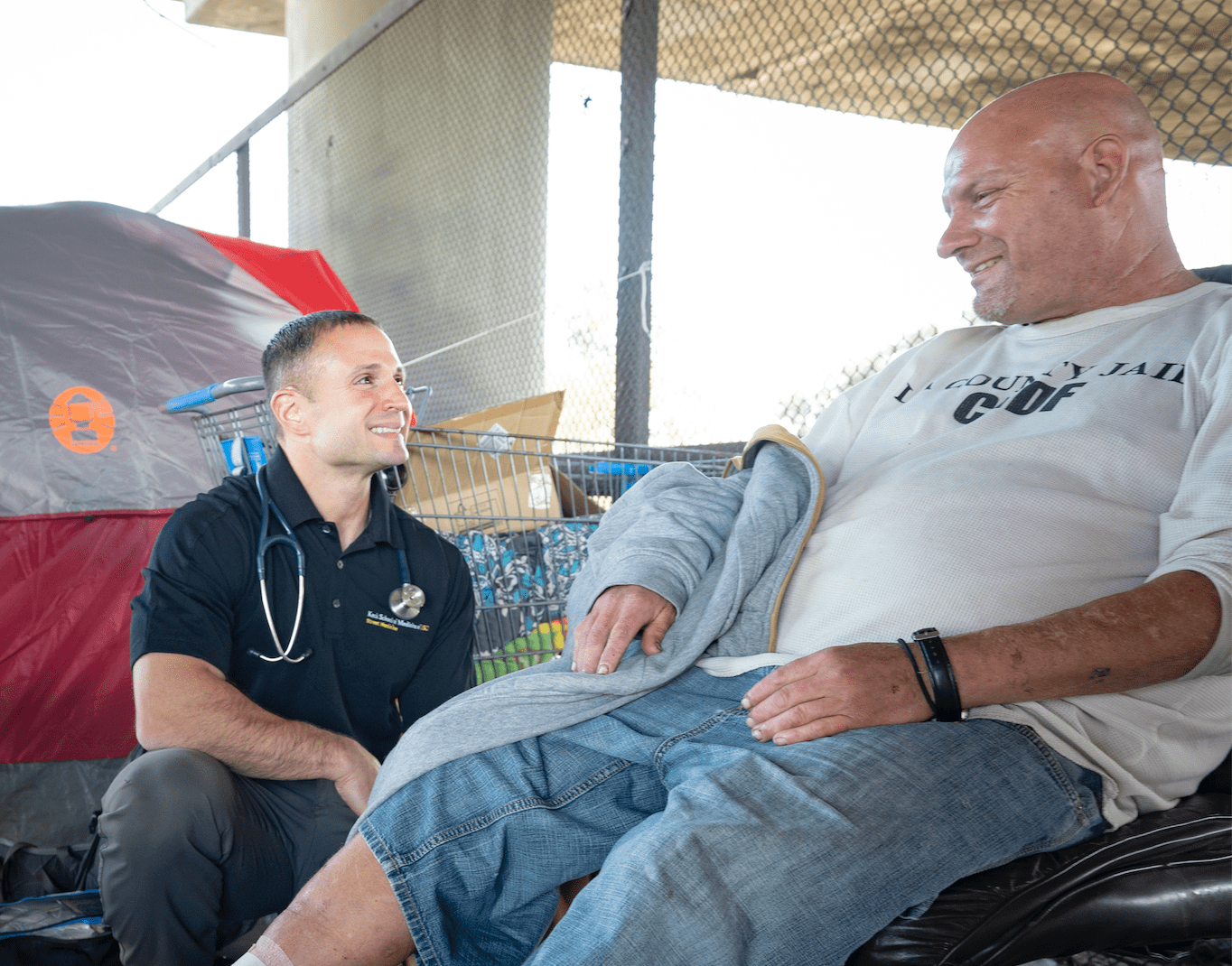

In a piece done by the BBC, a crew joins USC Director of Street Medicine Brett Feldman, MSPAS, PA-C and Gabrielle Johnson, MSN-FNP(c), BSN, RN, PHN as they do their rounds on a typical day. They visit with patients living on Skid Row and see the team treat a patient who lives under the train line in a bridge.

https://vimeo.com/user43082508/review/375459018/6b12d54ac2

Inaugural L.A. Street Medicine Symposium tells doctors: Go to the people

The homelessness crisis in Los Angeles can be described as a burning building: the latest count put the number up 12%, at 36,300 in the city alone. That’s the largest population of unsheltered homeless in the country, by far. To treat those patients on the streets takes a special kind of medical provider — ready to tackle the singular challenges of street medicine.

“We’re actually the ones on fire,” Brett Feldman, MSPAS, PA-C, clinical assistant professor of family medicine (clinician educator) and director of street medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, told a packed auditorium at the first-ever L.A. Street Medicine Symposium. In the past few years, Los Angeles has gone from two people practicing street medicine to 13, and from one organization to five — and all are ready for more.

During the daylong conference, held July 25 on the Health Sciences Campus, medical professionals from around the country learned about best practices for treating people living on the streets, from psychiatric medicine to quality assurance.

“Today is an important step in continuing to deliver health care directly to our neighbors, whether they are on the streets, under bridges or on the riverbanks, experiencing homelessness,” Laura Mosqueda, dean of the Keck School of Medicine, told the audience. She added that Keck Medicine of USC has a long history of programs designed to serve those who are on the margins of society. For example, Keck School medical students team up with students from occupational therapy, social work and pharmacy to provide health care on Skid Row. “We’re all in this together and each of us has an important contribution to make,” Mosqueda said.

The L.A. Street Medicine Symposium was presented by the Department of Family Medicine and the USC Office of Continuing Medical Education. The L.A. Street Medicine Symposium is an essential step toward developing a workforce ready to serve our neighbors living on the street, organizers said. (Photo/Ricardo Carrasco III)

People living on the streets suffer tangible medical problems: the average life expectancy is 42-52 years unsheltered, but 78 years for someone who is housed. The leading causes of death for a person living on the streets are cancer, heart disease, chronic substance abuse and drug overdose.

Street medicine is unique in the medical world because the care has to be delivered out of the clinic, directly to the unsheltered homeless, Feldman said. Providers do rounds to their patients on foot (or occasionally on horseback or kayak) while carrying a few backpacks full of medical supplies. Medical care also is an instrument of peace and a tool for advocacy. “We are going to a war-torn area with traumatized patients,” Feldman explained. He added: “More important than any of the medicine, we bring hope.”

Liz Frye, MD, MPH, director of psychiatry and street medicine at Mercy Care, an Atlanta-based homeless health care center, told the audience how best to practice psychiatric care for the unsheltered homeless. She explained that street diagnosis often meant using the same medicines — but different type of diagnosing. Instead of taking an hour to do a complete psychiatric workup, Frye often does a rapid assessment in 15-20 minutes and adjusts the diagnosis on subsequent visits. She prescribes a small amount of medication (so it won’t get lost) and checks in often with her patients.

“Practitioners should always weigh risk of exposure to the streets and the risk of treatment,” she said. “Above all else, the most important thing you do is build trust with the people who are sleeping outside. Focus on the person’s needs, check your own agenda.”

— Katharine Gammon

Researchers develop tool to standardize clinical outreach to homeless

Researchers from the street medicine team at the Keck School of Medicine of USC have developed “HOUSED BEDS,” the first published tool designed specifically to help outreach teams clearly assess the situation of unsheltered homeless patients. This memory-prodding acronym can help clinicians ask high-yield questions and gather vital information necessary to providing quality care tailored to the needs and lifestyles of patients living on the street.

“An important first step in helping homeless patients is to clarify the social, mental and physical challenges they face living on the street that can vary drastically between individuals,” said lead researcher Corinne T. Feldman, MMS, PA-C, clinical instructor of family medicine at the Keck School. “HOUSED BEDS empowers clinicians and students to incorporate information like access to sources of clean water, food and other services into a homeless patient’s medical history.”

“HOUSED BEDS” stands for:

Homelessness: Patient’s history of homelessness

Outreach: Who else is providing services

Utilization: How patient uses health care, social services and judicial system

Salary: Kinds of financial resources

Eat: Sources of food and access to it

Drink: Sources of clean water and access to it

Bathroom: Access to toilet

Encampment: Sleeping environment

Daily routine: How to minimize competing priorities

Substance use: History of usage

This acronym is designed to spur clinicians to ask questions they may not have been trained to ask, which can reveal issues that directly impact a patient’s health.

“Developing an effective treatment plan depends on a complete and accurate patient history,” said Brett Feldman, MSPAS, PA-C, clinical assistant professor of family medicine and director of street medicine at the Keck School. The street medicine program administers care to homeless individuals in Los Angeles County, which is home to nearly 45,000 unsheltered individuals. “Even patients in traditional clinic settings omit information, sometimes unintentionally, that could be relevant to a diagnosis, so it’s important for outreach teams to have a means of understanding each homeless individual’s unique situation,” he added.

Learn more at https://osf.io/2qb3h/

New grant will support training clinicians to care for vulnerable populations

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) has awarded a team at USC $1.5 million to enhance primary care training for physician assistant students, in an effort to support future clinicians to work with vulnerable populations, support wellness in providers, address inequities in health care and provide proper training to tackle the growing opioid crisis.

“The grant allows us to empower our students so that they have the right tools and resilience to facilitate change,” shared Corinne Feldman, MMS, PA-C, clinical instructor of family medicine (clinician educator) at the Keck School of Medicine of USC and principal investigator on the grant.

The grant focuses on implementing and studying programs related to street medicine and social justice over the next five years within the Primary Care Physician Assistant (PA) Program curriculum. Titled, the Project for Underserved Equity-Based Primary Care Education (USC-PeaCE), the grant will begin with the creation of a pipeline of PA students equipped to provide primary care to underserved populations with an emphasis on unsheltered homeless individuals.

“Our students already have a history of graduating and working in underserved populations and the grant will allow us to better train them in the didactic and clinical phase by using the street medicine framework, for all of those vulnerable populations,” said co-principal investigator and director of street medicine at the Keck School, Brett Feldman, MSPAS, PA-C, clinical assistant professor of family medicine (clinician educator).

By integrating evidence-based course work into the PA Program, students can build skills and confidence in the areas of health equity, mental health and substance abuse disorders, including opioid addiction and systematic wellness for faculty, providers and trainees. Beyond the classroom, students will participate in targeted clinical experiences with a rotation in primary care street medicine to be piloted by the second year. Additionally, the grant includes funding for faculty development to enable the enhanced curriculum with emphasis on equity-based primary care and wellness curriculum.

A major part of the grant focuses on supporting scholarships for veterans to matriculate into the PA program. Specifically, the HRSA grant funds a veteran community liaison, who will recruit and mentor veterans entering the PA profession.

“This is a new era of veteran health care and I think our patients will be better served by having veterans in the classroom and having them as part of our clinical rotations, especially on street rounds,” Corinne Feldman said.

Another element that the grant will support is funding the required training of students in medical assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid addiction. In addition to the X-waiver training, students will be exposed to responsible practices for prescribing opioids in their didactic phase, get firsthand knowledge of the use of opioids on the street and work with health care providers who specialize in this area.

“The ideas of diversity, equity, vulnerable populations and social determinants of health are incorporated into most medical schools already, but the problem is when our students graduate they see patients with vulnerabilities and their expectation falls short of being able to impact our patients, which leads to moral distress and burnout,” Brett Feldman reflected. “We are teaching future providers to be prepared for that.”