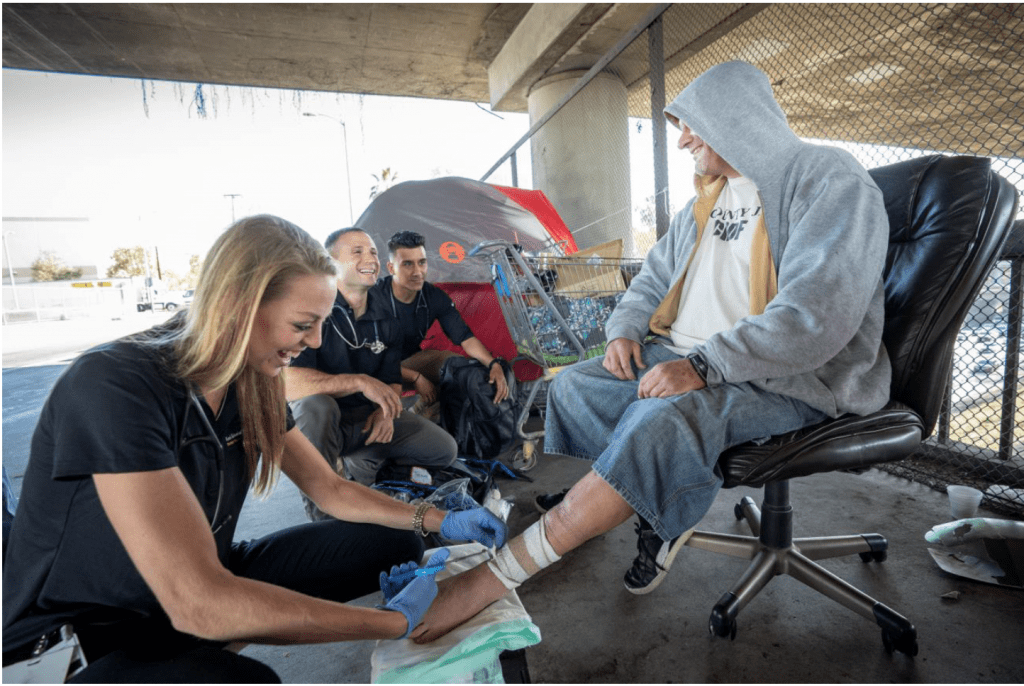

Homelessness has grown to epidemic proportions in California. In Los Angeles County alone, more than 52,000 people are homeless. The vast majority of homeless people are not living in shelters and have little to no medical care available to them. Street Medicine serves the homeless community by providing direct care on the streets and under bridges to the unsheltered and hardest-to-reach populations. All care is provided free of charge and delivered onsite, including dispensing medications and drawing blood for testing. The Street Medicine movement has grown exponentially in recent years and is now active in more than 60 American cities. Not only does Street Medicine offer care –often lifesaving care– but it also reduces costs for communities by addressing many health concerns before they intensify.

USC has named homelessness as a priority in need of unique and innovative solutions. Research has shown that among people who are homeless:

- Average life expectancy is 42-52 years; it is 78 for housed individuals 1

- 38 percent have two or more major medical illnesses 2

- 25 percent have a severe mental illness 3

- At least 30 percent have a current drug-use disorder 3

The Keck School of Medicine of USC Street Medicine is an emerging collaboration of interdisciplinary healthcare professionals that aims to improve care for the homeless while advocating for healthcare justice in Los Angeles through medical and social service outreach and research. The city’s homeless encounter numerous barriers to primary healthcare despite experiencing a disproportionate burden of acute and chronic health issues. Under the direction of Brett Feldman, MSPAS, PA-C — an internationally recognized expert on Street Medicine– our program offers services that address the circumstances that undermine the mental, physical, and emotional well-being of our city’s homeless.

Street medicine includes health and social services developed specifically to address the unique needs and circumstances of the unsheltered homeless. The fundamental approach of Street Medicine is to engage people experiencing homelessness in their own environment and on their own terms, with the goal of maximally reducing or eliminating barriers to care. The emphasis on unsheltered or “rough sleeper” homeless populations is intentional, as they experience increased morbidity and mortality in comparison to sheltered homeless populations.

Keck School of Medicine (KSOM) of USC Street Medicine recognizes that the unsheltered homeless, due to their preoccupation with survival, face barriers accessing traditional healthcare, especially through standard entry points. This has led to care being brought to the patient in their environment. The moniker of the Street Medicine Institute is to, “Go to the people,” with care being delivered on-site in homeless camps and physically on the street. Bearing witness to these unique environmental factors, drug use, and access barriers frequently leads to a change in the care plan and overall health of those we serve.

Perhaps most importantly, Street Medicine aims to break the most difficult barrier, one of trust. It’s important to, “Go to the People,” but it is also important to stay with them. Successful street medicine involves sharing in patients’ suffering by standing in solidarity with them as they attempt to survive the day. This may involve helping to shovel snow after a tent was destroyed in a storm or riding a bus side by side with a patient and enduring the harassment from other passengers together. The aim is to be truly patient-centered. This type of relationship and these types of activities are essential for the success of street medicine patients. Proving trustworthiness requires being trustworthy. Without creating trust, nothing else will be successful. KSOM Street Medicine recognizes the value of this bond and maintains a constant presence on the street.

1. O’Connell, J.J. “Premature Mortality in Homeless Populations: A Review of the Literature.” 19 pages. Nashville: National Health Care for the Homeless Council, Inc., 2005.

2. Lebrun-Harris LA1, Baggett TP, et al., “Health status and health care experiences among homeless patients in federally supported health centers: findings from the 2009 patient survey.” Health Serv Res. 2013 Jun;48(3):992-1017. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12009. Epub 2012 Nov 7

3. Lehman AF, Cordray DS. Prevalence of alcohol, drug, and mental disorders among the homeless. Contemp Drug Probl 1993;20:355-83