By Annabelle Asali, B.Arch Class of 2023

Recipient of the Chiu Man and Maria Warner Wong Global Traveling Fellowship Fund in Sustainable Architecture

As an American-born Chinese Indonesian daughter of immigrants, I’ve struggled to connect with these identities throughout my life. This trip was the pinnacle of my education where I could finally experience the intersection of my architectural career with a sentimental adventure that I’ve always wanted to undertake. When I was younger, I studied Balinese culture as a dancer, but I never really understood what life was like there or what it meant to celebrate Balinese culture and tradition.

As I embarked on the 1.5 month course of my trip, I narrowed down the lens of what I was really searching for: hospitality, as an industry where developing architecture is a by-product for tourists, and hospitality, defined by how people and places can be generous and welcoming to an individual in the face of a new environment. When it comes to understanding a new place, both are equally important in how we, as architects, begin to re-define hospitality.

Prior to the trip, I extensively researched Bali, the intricacies of the tourism industry, and the glaring reality that 80% of the population relies on tourism as its main form of economy. This reliance on tourism isn’t new. Indonesia declared Bali an international tourist destination in the 1970s, which led to mass development of large-scale resorts that began to overtake the most well-known cities in Bali: Nusa Dua, Uluwatu, Seminyak, Kuta, Canggu, and Ubud. Although tourism started as a beautiful homage to sharing the culture and traditions around Bali, over the past 20 years, this once paradise island has started to become unrecognizable by everyone I’ve talked to. The harsh reality is that Bali lost much of its infamous charm and beauty due to the symptoms of over-development, poor infrastructure, disrespecting tourists, and inflation of prices. Bali has been commodified. My goal was to find the true spirit of Bali and to identify successful examples of hospitality in this place.

Bali Untouched vs. Bali Developed

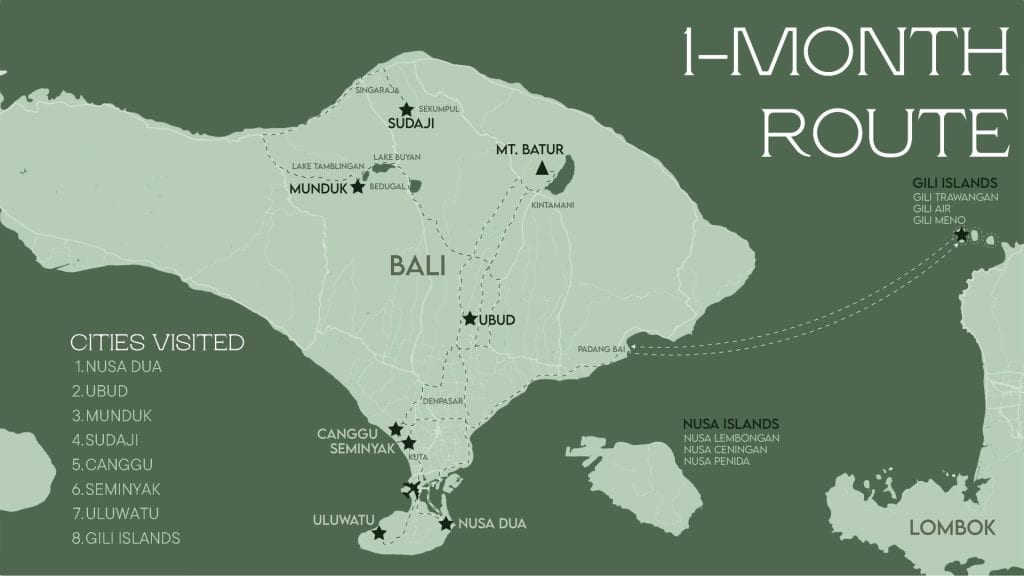

My trip entailed staying at a variety of housing accommodations: hostels, homestays, and hotels. By experiencing both ends of the spectrum, budget vs. luxury, I got to see what authenticity remains for tourists. I visited around 8 locations across the island where I pieced together what Bali looked like before development and compared it to the booming tourist destination it is now.

A large part of understanding the beauty of Bali is being immersed into its natural landscape. From waterfalls, black sand beaches, volcanoes, jungles, to rice terraces, lakes, mountains, Bali truly has it all. By seeing these various landscapes across the island, I realized the large responsibility we have as architects to highlight and prioritize the maintenance of our environments.

The highlight of my trip was visiting the areas of Bali that have remained untouched by tourism. I visited Munduk, a city that opened itself up for tourism more recently, which is located between two lakes above Bali’s agricultural hub and is home to only 6200 people. I stayed at a family-owned hostel that only houses 6 travelers at a time. Because I couldn’t drive a moped safely up steep winding roads, I traveled by foot, hiking through the jungle to chase some waterfalls. It was half-way through my trip when I got to experience the authenticity of Balinese people, where its residents did not sell me tourist attractions, but rather wanted to share the beauty of where they live with me. I could walk freely without the worry of guarding myself from consumerism, and instead, I opened myself to conversations with locals while exploring the variety of waterfalls in the area as a young, solo female-traveler.

Views from my hiking trail in Munduk. Golden Valley Waterfalls.

Gili Islands, similar to Munduk, is not quite touched by tourism as intensely as other parts of Bali. Off the coast of Lombok, these islands are home to rolling mountains next to the clearest ocean where sea turtles and healthy coral live.

Another very unique stay was in the Sudaji Village, situated in the northernmost tip of Bali. As an ex-hotel employee in Bali, my host created authentic experiences and cultural immersion within his home village. He invited me for 5 days to stay at his bamboo eco-resort compound called OmUnity (designed by Ibuku), where I had the honor of attending 3 Balinese Hindu ceremonies. The mission of OmUnity was to promote ecotourism, where the goal of hospitality experiences is to benefit the people of his community and give tourists a chance to participate in traditional Balinese traditions many people don’t get the opportunity to see. Because it is so isolated from the rest of the island, OmUnity also provides visitors with the experience of unplugging from regular civilization. While these religious rituals were quite intense and intimidating at times, there was also a beauty to being embraced by an unknown community and being treated with the utmost welcome.

Attending the annual Rice Festival ceremony at the village temple in Sudaji.

The last accommodation that embodied my idea of Bali Untouched is the infamous Amandari. As one of the first luxury hotels on the island, it used a hotel business model that fully integrated its community as one with the hotel. I received a personal tour of the grounds by Radit Mahindro, a passionate Balinese hotel historian, who runs the marketing for the Aman Group in South East Asia. He shared with me the design considerations that architect, Peter Muller, made where he based the typology of the resort to be a reflection of a typical Balinese village. One of the highlights of the resort is that it’s built around an unobstructed axis that runs through the entrance down into the valley where the village makes pilgrimages down to pray to a statue

Unobstructed axis through the resort.

While the experiences listed prior revolve heavily around the connection with Bali’s natural landscape, there are still other hospitality projects in populated tourist hubs that embody the true spirit of Bali. However, this section, Bali Developed, takes a more critical lens on how Bali as a place struggles with its over-touristic image. With an unassuming location in busy Seminyak, lies Desa Potatoheads, designed by OMA. Famously known for their program diagrams, OMA integrates a wide variety of programs including a hotel, beach club, spa, library, restaurants, and various fluid performance spaces. Its beach club and cultural arts bring in travelers and locals together creating a tight-knit community within the larger one. One thing the hotel does really well is integrate guest activities with the locals — including curated cooking classes with home-grown chefs, volunteering and teaching children, plastic clean-ups, mangrove conservation, and waste management tours. I wholeheartedly agree with its distinction as one of the World’s Top 50 hotels in 2023 due to its beautiful design that pays homage to Indonesian materials and Balinese courtyards. It successfully connects the concept of luxury and comfort while creating a new public space for travelers and locals alike to gather away from the bustle of the crowded city outside.

Two of Bali’s biggest natural attractions, Kanto Lampo Waterfall and Mount Batur, are known for their infamous beauty. I found that the unavoidable popularity of these attractions detracted from their innate beauty. Kanto Lampo is unlike most waterfalls I visited because its water looks like it is a mist that rushes down like rainfall. However, one can’t ignore the line that wraps from the head of the waterfall down and around the creek due to the mass hysteria of getting “THE instagram photo,” preventing people from really enjoying the sounds of the water falling and being able to interact with the water. Mount Batur is one of Bali’s active volcanoes that has a stunning view of the island at sunrise. Especially when the conditions are right, the clouds hover just below the peak of the opposite mountains creating a view like you’ve been airlifted into heaven. I hiked 1717 meters up the mountain at sunrise, only to find that the whole way up was a crowded line of non-stop tourists. There was no breathing room to make a mistake nor was there really a space for you to stop and take a breath. The only way was up, and the view at the top was breathless, literally and figuratively speaking. Although I cherish these experiences, I couldn’t help but notice that Bali continues to struggle with its mass tourism and the endless cycles of visitors taking away from the natural state of these popular areas and environments.

Kanto Lampo Waterfall. Mount Batur.

Learning from the Environment

I visited the renowned firm Ibuku’s project, Green Village, a neighborhood where each villa was uniquely designed and constructed with bamboo alone. I also spent time learning the processes in which bamboo is selected and treated to become the most sustainable building material in Bali. While there are over 1600 species of bamboo that grow in Indonesia, the two most common I came across are bambu tali (used for construction, furniture, walls, etc.) and asper (used for big structures). Bamboo is one of the fastest growing natural structural materials. It takes 1 year to grow vertically, 2-4 years to grow horizontally for the base to widen, and by 3-4 years old, the bamboo is ready to harvest. They are treated in either a cold or hot treatment of boric acid, which allows the bamboo to last around 30 years. Without treatment, bamboo would only last 1-2 years. This renewable material is the future of the building industry, and Bali is one of the leading specialists in this type of construction design.

Diagrams from IBUKU’s Bamboo Factory.

While visiting Sudaji Village, I also learned more about the subak system, a farming irrigation system that’s been used since the 12th century where water is collected and dispersed across Bali through a cooperative social system led by village political leaders. Following Hindu beliefs of “Tri Hita Karana,” the idea of balance between human, nature, and god, the Balinese subak system is the lifeline of Bali’s agricultural infrastructure. It was explained to me that the water is collected in a concentrated water temple from the lakes of Bali and because Bali’s elevation slopes down from the northern tip, the water moves across springs and rivers into the terraced farming for produce like rice, vanilla, cocoa, cloves, snake fruit, coconuts, and more. For years, this system has been studied by researchers and is even named a UNESCO heritage site. Seeing how this widespread system spans across the island stressed the importance of teamwork and cooperation required by the Balinese villages and its people to make sure there is enough water for all its municipalities to participate. I was again reminded that the environment commands respect and responsibility towards our natural resources.

Rice terraces that use the subak system to carry water from the top going down each terrace and across each farmer’s plot of land.

Hospitality in Bali and Beyond

As I redefined Hospitality in Bali, I recognize that the industry requires a compromise between the two ideas of being untouched and developed. The future of Bali is rapidly progressing in response to an increase in tourism, but as we continue to design spaces, there needs to be an emphasis on representing the true spirit of Bali rather than the marketable touristic one. Bali’s successful hospitality design strategies include: bamboo construction, comfortability with darkness, sacred religious ideals of axis symmetry, integrating village typology, and most of all, embedding architecture into nature. The use of these ideologies is only one part of the answer. Hospitality goes beyond the design, but includes the spirit of its people–like the warm welcome the locals and travelers gave me in their communities. I befriended so many interesting people: homestay owners, budget travelers (solo and group), soul-searchers, luxury vacationers, 7+ local drivers that took me to every new city/destination, keepers of waterfalls, female tour guides (something unheard of in SE Asia), long term tourists turned residents, digital nomads, Balinese teenagers, and so many more. From my education, I was taught that architecture is always rooted in place. But more importantly, these places wouldn’t be what they are without the conversations and hospitality I felt from these people.

After culminating my trip, I arrived back in Los Angeles right in time to start my first job out of school at an architecture firm. Working as an architectural designer in the hospitality sector, I’ve realized this trip has brought my experiences full circle as I am now working on projects that create authentic and unique experiences that push the boundaries of hotel architecture and make these places hospitable. The beauty of Bali touched every thought and perspective in my life, from how I see things to the way I approach the world and will design for it. I’m so thankful for this opportunity to travel and redefine my identity rooted in these experiences.