Danann De Alba, B.Arch ’23

My journey begins in Oslo, but there is no time to spare. You see, I am not here to visit great cities and picturesque towns. No, I am here to find what it means to build in remote and sensitive landscapes, where the architect must face, and perhaps even embrace, the challenge, and the opportunity, of designing for a natural landscape so overwhelmingly dominant that it dictates not just the language and palette of the architect’s work, but the very act of construction. I follow the Norwegian Scenic Routes, where architects have been invited to design unique interventions each responding to their landscape, witnessing the many unique landscapes and architectures along the way, and sometimes going off the beaten path to find

the most remote and architecturally distinctive cabins to stay in.

On the first part of my journey, I go inland. When thinking of architecture in natural landscapes, I often think too of the architecture of manmade landscapes. They are closely linked, after all. Our industrial activities have huge impacts on the natural environment; we create landscapes anew and often destroy those that once existed. However, we can also find new opportunities from industrial landscapes; we can build within them, we can be inspired by them, we can learn from them. That was the topic of my thesis. That is why as much as I am researching natural landscapes in Norway, I am also looking into those built by man. On the first day, in Telemark,

we see a lot of Norway’s architectural curiosities: a medieval Stave Church, Canals and dams, hydropower, a sauna on a lake, a winding path above the trees.

Next I travel along the southern coast. Here, landscapes contrast. Massive bridges, hydropower dams and titanium mines are interspersed among quaint seaside towns and cliffside huts. Mountains give way to wide coastal fields, where seaside pavilions, lighthouses, and earthen homes (an architecture of the landscape that protects from the strong winds of the region) fit right in. Towards the end of the day, I cross the world’s second longest road tunnel, and as the sun begins to lower (after 9 pm, this is Norway, after all) and with dreadfully increasing precipitation, I hike towards a set of cabins so remote and so architecturally unique, I can’t help

but think “How did these even manage to get here?”

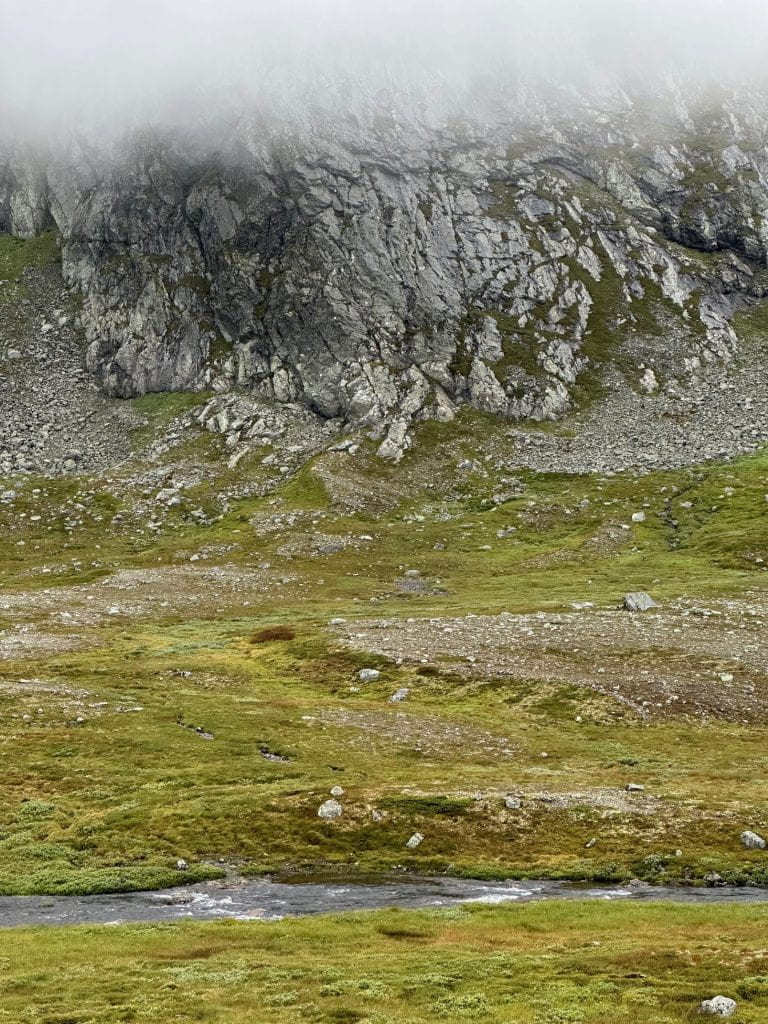

The following couple of days involve an increasingly rugged landscape. Now we begin to truly experience the beauty of the Fjords. Echoing the massive bridges, power plants and tunnels used to cross these fjords and harness their power, are the pavilions I visit along the way: pedestrian bridges, concrete sculptures and steel on stone. I cross a one-of-a-kind brutalist hydropower station worthy of a movie supervillain, on my way to another remote modern cabin set into a landscape straight out of a fairytale. Soon, Norway’s temperamental weather catches

up with me as I cross the highlands. Here, I witness a landscape that I can only describe as otherworldly. The weather makes it all the more surreal. As I leave this amazing landscape I find myself in a deep ravine, and hidden within it is my destination: Zumthor’s Zinc Mine Museum; an amazing piece of architecture that perfectly combines modern sensibilities with a deep respect and reflection of the history it is building on.

Next we enter the Hardangerfjord. Glaciers and waterfalls on one side, Norway’s largest hydropower plant on the other. Calm water and huge industrial facilities in the middle. Just past the end of the Fjord, and past some of the most impressive winding tunnels imaginable, lies Norway’s most iconic waterfall: Voringfossen. Here, the chasm is literally bridged by an impressive and quite creative set of architecturally distinctive bridges and cantilevered viewpoints. Here the feat of the architect is almost as much of a show as the natural wonder, for better or worse. To continue the journey, it is necessary to cross the Fjord. For that, they built

one of the longest bridge spans in the world. The Hardanger Bridge is, like the waterfall, a sight to behold, a wonder of engineering and infrastructure architecture.

The journey across Hardanger Fjord, past many waterfalls and seaside cliffs, leads me to the city of Bergen, by the North Sea. Whilst Bergen is a popular destination, and the World Heritage Bryggen harbor is quite incredible, after a quick stop I must continue back up and over the mountains. Soon I am traveling along the inner branches of the Sognefjord, Norway’s largest and deepest Fjord system. On my way up to a highland valley cabin, I get occasional peeks into the UNESCO World Heritage Nærøyfjord.

The next section of the journey, the Aurlands Mountains, has been made obsolete by the world’s longest road tunnel which cuts through 25 kilometers of the base of the mountains. I am, however, taking the old, scenic route, with its iconic views, barren, snowy mountaintops, and unique architectural pavilions. The way back down from the highlands has me witness the last Fjord before I head inland. In those valleys I stop to experience another of Norway’s iconic Stave Churches at Borgund, before resting in another mountain cabin.

I spend the next couple of days traveling and hiking through the Norwegian highlands, with great peaks in the distance. This area is less rugged but perhaps more wild and remote. The solitary expanses of tundra, with cabins interspersed at convenient distances, prove quite inviting for the long-distance hikers I encounter out there. Before I head back to civilization, I head for the last highland plateau, where a terrifying thick fog makes for a surreal and otherworldly landscape; and a perfect place for a fireside Hot Chocolate at a café-turned-architectural-experiment. On my way back towards the forests and fields of inner Norway, I stop overnight at another modern cabin, whose peculiarity is not in its uniqueness but in the fact that it is an example of a new form of modular prefabricated cabin that facilitates

assembly in remote areas.

As I approach the final leg of the journey, I witness the return of civilization. I spend some time in the town of Hønefoss (which had just witnessed some of the worst flooding seen in Norway this century), visiting the Kistefos Museum and Historic Mill. Part sculpture park, and part historical site and museum, and part nature reserve, it serves as a great example of adaptive reuse, and of combining nature, industry and art. It is well known internationally for being the site of the iconic Twist by Bjarke Ingels Group, which much like the rest of the park, serves a triple role, as

museum, river crossing and iconic centerpiece of the site.

Finally, I finish my journey with a few days in Oslo. As a city that is not afraid of architectural experimentation, Oslo is host to both some remarkable pieces of architecture, including perhaps the coolest and one of the most beautiful Opera Houses in the world, great examples of adaptive reuse, from the train station, to the library and to the Peace Center, and some impressive contemporary museums, as well some wacky projects that may have gone a bit too far. This is on top of its fair share of historic districts and architecture, and unique historical experiments in art and architecture too. In many ways Oslo reflects the quirky mix of a traditional, humble history, and an experimental, ambitious and modern spirit that is present

throughout the country. In this way, Oslo proves a fitting end to my time in Norway. While it was not easy traversing half a country through rugged landscapes and intense weather, it is all worth it, because what better inspiration for the work of the architect can there be than the beauty of nature and the pursuit of seemingly impossible feats of architecture in the wilderness.