Justin Wan, B. Arch ’22 -Recipent of the Jon Adams Jerde Traveling Fellowship

An antagonist in the fight against climate change is the collective lack of obligation to protect the environment, whereby humans see themselves as separate from nature. My research examines ways of strengthening human connection with nature by challenging biophilic architecture in the way it creates an idealistic depiction of natural landscapes that in turn intensifies the disconnection, or, as it is known, biophobia. Biophobia is innately tied to the emphasis on protectiveness ingrained in urban environments, which became more prominent during the COVID-19 pandemic as growing concerns over the virus have spiked a surge in material consumption to keep living spaces clean. The environmentally damaging practice of creating sterile environments has made our bodies accustomed to protection, resulting in negative psychological reactions from contact with foreign stimuli. Studies on biophilia become an opportunity to reevaluate the relationship between natural and built landscapes, allowing me to reimagine architecture as a tool for improving human responses to nature.

In the winter of 2022, I had the opportunity to travel to Tokyo, Japan to explore the ways nature and its constituent elements are integrated into the Japanese culture and customs, and in turn, influence Japanese principles of aesthetics and perception of space. The two-week trip focused on two main areas of interest: 1.) Traditional Japanese social customs & ritual mannerisms and 2). Japanese architecture, to delineate the intrinsic connection between design and nature. The sites visited during this trip compare traditional buildings with contemporary examples, revealing Japanese architecture as physical manifestations of traditional values as these virtues persist through time.

Religion

To begin, I should first note that Japan is a religious country with ideals influenced by two major doctrines, Shinto and Buddhism. Being an archipelago nation, Japan is made up of 14,125 islands with which approximately 70% of its land areas are covered with forests and trees. The diverse range of climates, terrains, and landscapes has given rise to the indigenous religion of Shinto (神道), or nature worship, where supernatural entities and forces are believed to inhabit all living things and gestures. In this sense, nature becomes the greatest agent in inspiring the Japanese way of life. While Buddhism was later introduced to Japan in the 6th century, religious syncretization has made both religions practically inseparable and promoted ideologies of similar views. In both religions, the notion of Mujo (無常), or impermanence, forms the overarching theme of the Japanese attitude to life, whereby the awareness of the transient nature of life highlights the beauty in impermanence. In this sense, the passage of time and traces of constant change are celebrated, and the juxtaposition between life and death, light and dark, gives meaning to one another. The fleeting moment of sunrises and sunsets, the metamorphosis of chrysalises into butterflies, the wilting of blossomed flowers, and the decay of trees all exemplify the impermanence of life. While these ideas are frequently witnessed in the natural environment, Japanese society has integrated these ideals borrowed from religious teachings into their customs and outlooks on life.

Eight Manifestations of the Japanese Aesthetic

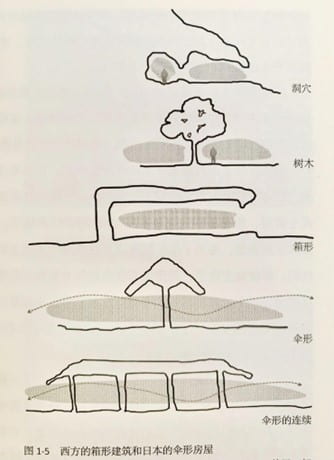

In light of the previous discussion about religious teachings and per, I frequently visited ideas discussed in Eight Manifestations of the Japanese Aesthetic by Kurokawa Masayuki, which examines the intimate relationship between design principles and the Japanese consciousness of the natural environment. The text defines the intrinsic connection humans share with nature as an outlook on life through exploring the eight principles 微(bi)、并(hei)、气(ki)、間(ma)、秘(hi)、素(so)、假(ka)、破(ha). Kurokawa compares Japanese architecture to vessels that emulate the ambiance of natural environments, the form of which originate from trees, where columns and roofs represent tree trunks and canopies. Interior spaces are designed to be fluid and open, with ample connections to the outdoor elements. On the other hand, ancient Western typologies which are inspired by cavern landscapes, are designed to keep the elements out and protect the inhabitants. As civilizations expanded through colonial means, the fortification of buildings intensified the disconnection between humans and nature, which the biophilia hypothesis argues against. However, contrary to the biophilia hypothesis that theorizes the innate human affinity for nature as a biological response, Kurokawa suggests how nature exists in multiple facets of Japanese traditions and gives rise to these eight principles. These principles are reenacted within the sociocultural aspects, and are likewise, embedded within the conception of architecture and design.

Cave-inspired Western Typology vs. Tree-inspired Japanese Typology

(Courtesy of the “Eight Manifestations of the Japanese Aesthetic” by Kurokawa Masayuki)

微(bi) defines the idea that details are not just parts of the whole, but in specific moments, represent a microcosm of the whole.

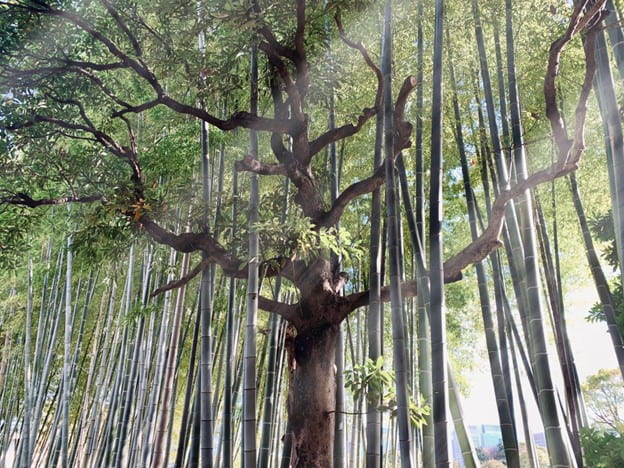

E.g. Individual trees are not seen as a part of the forest but as an ecosystem on their own that harbors other forms of life.

并(hei) defines the idea that details exist as microcosms of the whole, and therefore, can function autonomously alone and grow in aggregation.

E.g. Individual trees are microcosms of an ecosystem and can multiply to form new forests, communities, and villages.

气(ki) defines the distinctive aura or atmospheric quality, surrounding and generated by all life forms

E.g. Wood is seen as warm, and stone and concrete are seen as cold. Wood, therefore, gives out an aura of liveliness and vitality.

間(ma) defines mutual respect and harmony between life forms by displaying an awareness of personal space and thresholds

E.g. Acknowledging the presence of another animal or life form while maintaining distance and not disrupting the harmony by approaching or touching the animal. A bow or even a head nod are examples of Ma.

秘(hi) defines mysteriousness as giving freedom and space for imagination through the absence or partial concealment of the whole.

E.g. Fog can conceal, but can also allow for opportunities to imagine what is hidden behind. A forest? A ledge? An animal? Or nothing?

素(so) defines the beauty of purity and simplicity

E.g. Appreciating the materials in their purest form and the physical changes they undergo, such as the yellowing of bamboo, the cracks left in timber, the weathering of stone, etc.

假(ka) defines the acceptance of impermanence and the flow of natural forces

E.g. Leaving flowers and fruits fallen from trees where they are and willingly accepting the natural processes to take place, whether to sprout a new plant or to wilt and die.

破(ha) defines the beauty in organized chaos by breaking symmetry and objects in perfection

E.g. Pruning and maintaining the shape of bonsai trees but leaving certain branches to grow to achieve a more natural appearance.

These eight principles display the significance nature plays in influencing Japanese culture, and it is precisely this relationship with nature that such ideals have become incorporated into every facet of Japanese living. Order is installed by embracing the impermanence of life and coexistence between perfection and that which breaks it. Architecture becomes a tool to echo the designers’ response and personal approach toward nature, people, and life.

These eight principles have helped foster a deeper understanding of how “nature” is defined in Japanese culture and design. In this light, nature is no longer limited to describing life forms or that which came from natural processes, but could also be used to describe gestures and attitudes learned from nature. The poeticism of the approach to life and design became a new direction in my research to eye-witness how these philosophies are reenacted in real time and space.

Nature in Traditional Architecture

Looking at examples of traditional architecture in Japan, I was particularly interested in the entryways, and thresholds as they delineate contrasting ideas: that of light and shadow, indoor and outdoor, yin and yang, whereby one would not exist in the absence of the other, and connect humans to nature.

門(Mon), or gate, is an important feature of traditional Japanese architecture that serves as a signifier of entryways, space, and directionality in religious spaces. Often built out of wood, Mons are believed to have purifying and cleansing properties, which are placed along the processional pathway that leads to the Shinto Shrine. While Mons are traditionally a Shinto architecture feature, the religious influence is evident in Japanese Buddhist architecture. The Mon at the entry marks the transition from the human to the sacred realm and consecutive Mons are placed as markers to create a sense of anticipation for the inner sanctuary of the religious spaces. It is believed that the closer the Mon is to the inner sanctuary, the more holy the space becomes. The symbolic significance of the Mon demonstrates the entanglement between nature and Japanese religions. Furthermore, architecture becomes a medium to continuously harness and perpetuate this intricate relationship between the two ideas.

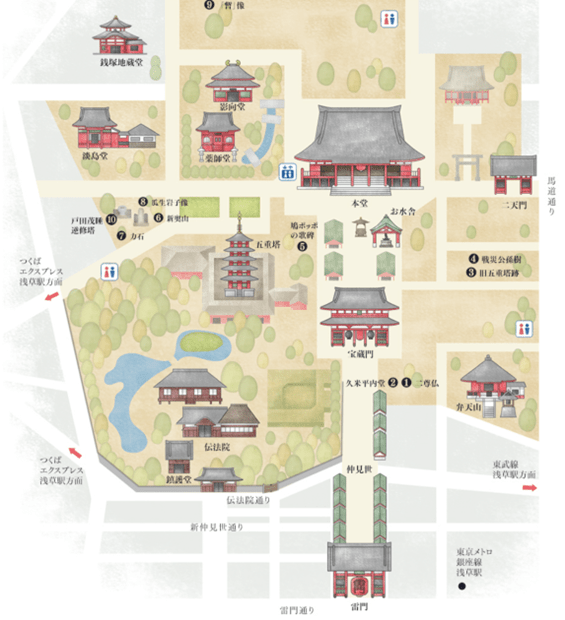

金龍山浅草寺(Kin Ryu-San Senso-Ji) Senso-Ji is the oldest Buddhist temple in Tokyo founded in 645AD. The temple ground of Senso-Ji houses numerous features belonging to Buddhist and Shinto architecture, including, gates, pagodas, and temples. Of all the buildings the precinct of the Senso-Ji has to offer, I focused on architectural features along the main axis of the temple ground, which includes features from the entrance gate to the center of complex: 1. 雷門 Kaminarimon (Thunder Gate) 2. 仲見世通りNakamise Dori (the street leading to the temple from Kaminarimon) 3. 宝藏門 Hozomon (Treasure Gate) 4. 金龍山浅草寺本堂 Kin Ryu-San Senso-Ji Hondou (Asakusa Temple Main Hall).

Precinct Guide of Kin Ryu-San Senso-Ji (Courtesy of Asakusa Kannon Senso-Ji)

Visitors are greeted by the Kaminarimon which marks the entrance gate to the Senso-Ji. The gate serves metaphorically as the threshold between humans and sacred grounds. It was believed that by traversing past the gate, one’s soul gets cleansed and becomes closer to god. Interestingly, on either side of the front elevation of the gate stands two statues of Shinto gods, 雷神 Raijin (Thunder God)and 風神 Fujin(Wind God), and two Buddha statues on either side of the back of the gate, 天龍 Tenryu (Sky Dragon) and 金龍 Kinryu (Golden Dragon). Despite this being a Buddhist temple ground, the statues and architecture display influences from the Shinto religion, showing the syncretization of religions mentioned before.

Picture taken outside of the Kaminarimon Gate

Pass the Kaminarimon is the Nakamise Dori, a street that leads visitors further into the inner sanctuary of the complex. Historically, the street is holy ground. Now, it is a popular tourist attraction filled with stores selling traditional foods and arts. At the end of the street is the Hozomon.

Traditional Red Bean Cake from Artisanal Store at Nakamise Dori

The Hozomon is the last gate leading to the Senso-Ji temple. Unlike Kaminarimon, Hozomon is a 二重門nijuumon (Two-story gate). The significance of the Nijuumon is that it provides additional rooms for storage and enshrining statues of deities. The gate has five rooms on the ground floor level, with two rooms on either end enshrining statues, and the rest are in the center of the gate used as passageways. On the second floor of the Hozomon gate are rooms that house two 20 feet tall Buddhist statues, treasured Buddhist Sutras, and scriptures.

Back elevation of the Hozomon gate

At the end of the street is Kin Ryu-San Senso-Ji Hondou, the center of the temple ground. In front of the temple entrance are incense holders and wells. These stations are used for cleaning purposes, to symbolize the act of cleansing oneself before entering the sacred temple. The hall itself is made up of three primary sancta which store the most prized Buddhist statues in the entire complex. Each sanctum is divided into 内陣naijin (inner sanctum) and 外陣 gejin (outer sanctum), where the naijin is used to enshrine and store statues and Buddhist scriptures, while the gejin is the space that visitors occupy before the altar to pray and pay respects to the Buddhist deities. However, since photos are not allowed inside the temple, only views of the temple front could be shown.

Front of the Kin Ryu-San Senso-Ji Hondou with incense burners and cleansing wells (right) & Western Corner of the Kin Ryu-San Senso-Ji Hondou (left)

On the way to exit the temple via its western doorway, I noticed the attention to detail in using its threshold as a device for framing specific views out from the temple. Situated in front of the Western elevation of the temple is a koi carp garden with a small prayer house next to it. The garden is designed to mimic traditional zen gardens with carefully curated features to create the illusion of a microcosmic landscape. From the temple’s point of view, the carefully framed scenery of the garden reenacts the principle of 秘(hi), whereby concealing the full scene of the garden beyond the frames of the door gives space for imagination and opportunities to ponder what the garden looks like. From the garden’s point of view, 并(hei)is reenacted where the curated landscapes become the physical manifestations of a microcosm, with flora and fauna, and the architecture of Buddhist-Shinto origins, serves as the backdrop of this scenery.

Garden in front of the Western elevation of the Kin Ryu-San Senso-Ji Hondou

靖国神社 (Yasukuni Shrine) Yasukuni Shrine is a Shinto Shrine built to commemorate those who died in service of Japan during wars from the late 19th to the mid-20th century. Serving as a form of memorial, the site has been a place of controversy as many of those commemorated are war criminals. However, the visit I paid to the site was strictly of genuine interest in the architecture and customs of Japanese culture. Similar to the Senso-Ji, the Yasukuni Shrine is designed with an informal precinct around it, and a main axis that connects the entry to the center of the precinct where the shrine sits. Trees are planted along the axis to mimic the natural environment where ancient Shrines were often built, located at the top of a hill accessible only by a thin path with gates placed at intervals along the path. Similarly, the entrance of the complex is marked by a Mon, or in the case of Shinto architecture, a 鳥居 torii (literal translation: bird abode), with an uphill walkway that leads visitors to the main shrine at the end of the path

Torii Gate at the main entrance of the Yasukuni Shrine & View of the inside of the Yasukuni Shrine

To reach the shrine, one must pass through three Torii, one at the entry, one in the middle, and one at the end of the pathway, and a Mon. However, the shrine displays architectural features that make it different from its predecessors. Traditionally, shrines are built as one long, continuous rectilinear storage space, with stilts that raise the building 6 to 8 feet off the ground to protect the architecture from moisture and vermin. These structures are protected from the rain with a steeply sloped, and wide-eaved overhanging roof thatched with rice straw. Either end of the roof spine is often ornamented with 千木 Chigi, forked roof finials. Torii gates are placed in distanced intervals along the pathway leading to the shrine. These features are often used exclusively on Shinto buildings and can be used to distinguish them from other Buddhist architecture. Interestingly, the configuration of the gates and main shrine of the complex does not appear much like that. Instead, features of the shrine typology are applied to one of the Mons, and the actual shrine appears with features closer to that of Buddhist architecture. The examples seen here make the architecture an interesting blend of Shinto and Buddhist designs.

Park Spaces

Nature is a huge part of the Japanese way of life, where parks are seen as pockets of spaces that mediate between the built and natural environment. Green spaces represent 24% of the land area in the city center of Tokyo and 52% of the land area in the Tokyo Metropolitan Area, with development underway to provide more green spaces for people. While Tokyo is Japan’s most developed city, the statistics come to show the prevalence of connection with nature within the country. The term 森林浴 shinrin-yoku (forest bathing) is a term coined by the Japanese, defining it as the act of immersing oneself in the atmosphere and air of the forest. To perform shinrin-yoku is to actively engage in appreciating all the elements nature could offer, the breeze, the moisture in the air, the temperature, the smell, etc. The Japanese believe that shinrin-yoku is an essential part of daily life that could help free our minds from stresses and burdens and heal our souls through the natural energy the forests give off. The next part of the research is to visit sites and experience the healing powers of nature.

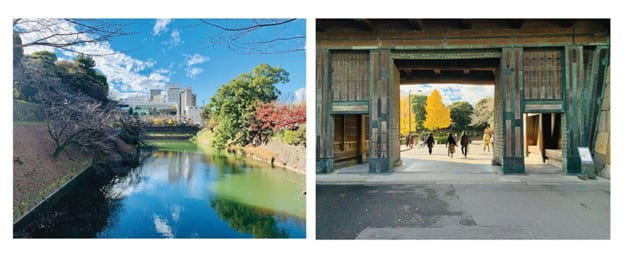

北の丸公園( Kita-no-maru Park)

Kita-no-maru Park, originally a medicinal garden and residential compound for members of the Tokugawa family in the Edo Castle, is a public park precinct. Given its past, the park is surrounded by deep moats with heavily fortified entries left from the original castle. The main entrance into the park is an artifact left from the original Edo Castle, made out of stacked stone with a wooden gate.

Moat at the Kita-no-maru Park Fortified entryway

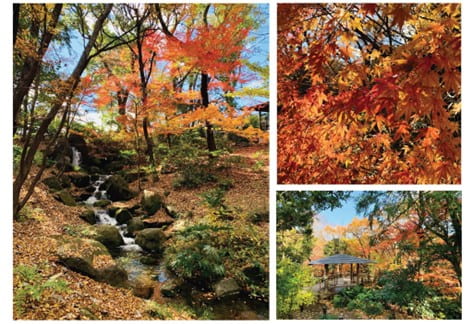

Within the park are numerous types of landscapes that create the illusion that the park is located in the countryside, rather than in the city center. As a part of my expedition to “bathe in the forest”, the diverse range of landscapes I came across has been a pleasant surprise the longer I stayed and wandered around the park. I was able to discover terrains such as deep tree forests, water features, bamboo forests, and even red maple left from the earlier season.

Bamboo forest Gingko Forest River Bend

The delight of walking through different parts of the park has allowed me a sensorial experience of the different ephemeral qualities nature offers through sight, hearing, smell, touch, and even taste. I was especially drawn to a pavilion located at the top of a hill overlooking an area full of red maple trees with the sound of a moving stream in the background. The sensation of looking at a canvas of diverse colors, the sound of running water, the smell of grass and trees, the touch of the wind, and the taste of maple in the air combined for a very therapeutic experience.

Pavilion on top of a hill overlooking red maple trees and a running stream

Nature in Contemporary Culture and Architecture

When studying contemporary examples, I was especially drawn to designs that demonstrate an association with nature whether by physical appearance, atmosphere, concept, or all of the above. The objective of the following expeditions is to understand how architecture has reimagined aspects of traditional typologies and incorporated ideas borrowed from nature into contemporary designs. Going off of the therapeutic properties nature has on humans, I visited buildings where the architect focused on harnessing the healing powers of nature through the designs. The next two buildings are designed by Hiroshi Nakamura & NAP as sister buildings to each other, one as a chapel and the other as a cemetery community hall, in Sayama of the Saitama prefecture.

狭山の森 礼拝堂 (Sayama Forest Chapel),

Hiroshi Nakamura & NAP

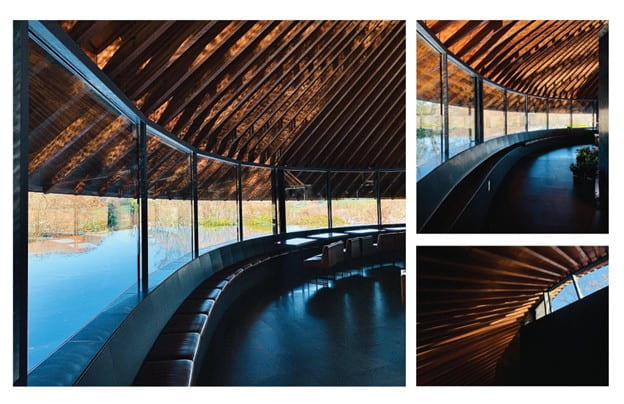

Sayama Forest Chapel is designed as a praying ground open to various religions and denominations. The building’s concept is derived from its environmental and site context, where the land sits adjacent to an existing cemetery. The site is located in a deep tree forest at the top of a mountain with huge ponds adjacent to the forest. Given the contrast between the blooming forest and the cemetery, the architect saw the site as a physical manifestation between life and death, where one gives, and the other takes. In the architect’s words, he “envisioned an architecture that reflects on the way of life as it lives by the water conserved by the forest, and eventually returns to this place after death.” The architecture became a point of neutrality that mediates between life and death on the site, acting as a place of prayers that allows the living to pray for the dead.

The design consciously avoids interference with the existing landscape and trees by tilting the walls of the building inward. The construction method is inspired by the traditional 合掌Gassho-style (Praying hands) structure but composed three-dimensionally with beams leaning against each other in an undulating fashion. The beam members extend to the floor to behave as both the roof and as columns of the structure.

Exterior and interior views of Sayama Forest Chapel

狭山湖畔霊園 (Sayama Lakeside Cemetery Community Hall)

Down the road from the Sayama Forest Chapel and past the cemetery is the Lakeside Cemetery Community Hall, designed as a space of meditation and resting for visitors of the cemetery. Although the location of the building overlooks scenic views of a lush forest from the top of the hill, the architect envisioned the design to have controlled apertures out into nature. The degree of closure is designed to reflect the idea of bringing closure to the friends and family of the deceased. The building exhibits aspects of shinrin-yoku where the concept of 木漏れ日komorebi (sunlight leaked from tree foliage) is actively employed to create an interior environment that is calming and warm. The building is arranged in a circular plan with controlled views open to the outside with a reflecting pool surrounding the building. The placement of the reflecting pool is both an operation to resonate with the local context of the nearby Lake Sayama and to enrich the interior spaces with water reflections cast on the ceiling of the building. In any instance, the movement of water could both be seen and heard. The circular plan of the building brings visitors from the entrance into the core where the roof beams slant down from the ridge to form a low-ceiling structure that is cozier and seemingly more closed-off. Near the top of the roof is a row of clerestories to allow komorebi to take place, where gentle sunlight is filtered through the forest trees and illuminates the interior of the building. The combined effects of architecture and nature become a healing experience for visitors that come to mourn the passing of their loved ones.

Interior views of Sayama Lakeside Cemetery Community Hall

Cultural Projects

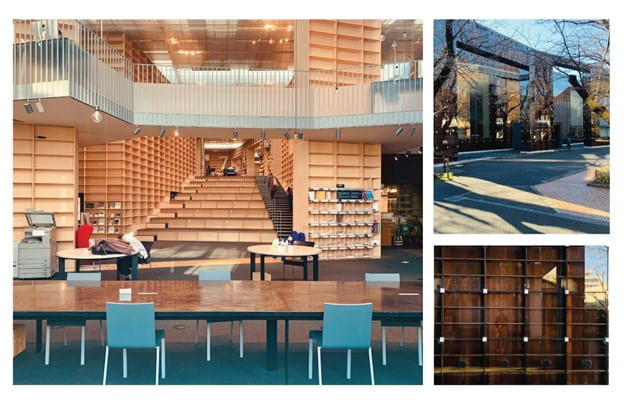

武蔵野美術大学図書館 (Musashino Art University Library), Sou Fujimoto Architects

The Musashino Art University Library rethinks the relationship between the activity of reading and space. The interesting aspect of the library is its primary structure in which the structural members are made from bookshelves. As the culture of reading slowly dies away at the wake of the digital age, the architect wanted the library to explore and manifest physically in itself how he imagined reading should feel, an endless whirlpool of knowledge and books. With that in mind, the interior space of the library is configured in the form of a spiral by bookshelves. The spiral eventually expands to wrap around the inner periphery of the building to allow the bookshelves to be seen from the outside, thus, informing visitors of the building’s interior functions. The interior spaces are arranged to allow the spiraling to occur across different levels, adding complexities to the architecture and making spaces appear more labyrinth-like. All primary structures of the building are made from wood to create the illusion that visitors are surrounded and sucked into a forest of books.

Interior & Exterior Views of the Musashino Art University Library

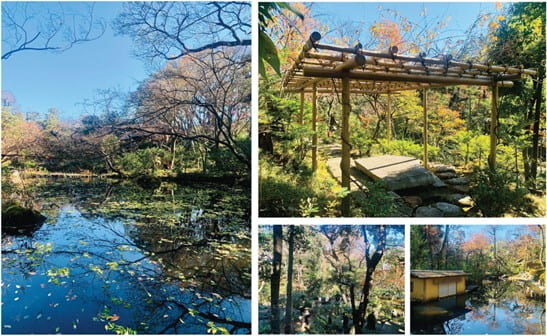

根津美術館 (Nezu Museum), Kengo Kuma and Associates

The current Nezu Museum is an addition of the original museum with parts of the building replacing the original warehouse for art storage. The Nezu Museum consists of the main gallery space, a landscape garden located behind the gallery, along with a hidden cafe in the woods. The entrance to the museum grounds is hidden from plain sight by a screen of bamboo. Only upon entering the complex does the passage leading to the gallery building become revealed, subtly immersing its visitors into a peaceful oasis away from the busy traffic adjacent to the site. The building houses a reception, a museum store, the main lobby, and two exhibition rooms. Since most of the artwork stored in the gallery dates back to ancient Japanese and Chinese cultures, the exhibition rooms are relatively dark to protect the artwork from sun exposure. However, the other spaces are well-lit by natural sunlight. By extending the overhanging eaves of the roof just above eye-level into the outdoor garden space, the boundaries between indoor and outdoor spaces are blurred, creating the illusion that parts of the lobby are outdoors in nature. The design operations used in the building to obscure the definition of indoor/outdoor encourage its visitors to move from the gallery space into the garden to enjoy opportunities for shinrin-yoku where the landscapes are designed to heal and bring peace to the mind and soul.

Nezu Museum in Minami-Aoyama, Tokyo

Views of the Nezu Museum landscape garden in Minami-Aoyama, Tokyo

微熱山丘 (Sunnyhills Minami-Aoyama Stor), Kengo Kuma and Associates

Sunnyhills is a cafe and dessert store designed with a bamboo lattice exoskeleton. Using a joinery system called 地獄組 Jigoku-gumi (literal translation: Interlocking Hell), bamboo studs in vertical and diagonal orientations are connected to form a muntin grid. Structurally, the joinery system makes for a very rigid shell. Aesthetically, the nest-like lattice allows natural light to enter the interior, producing the effects of Komorebi, where light is filtered through tree foliage. On the interior, the material choices of wood, paper, and bamboo create a warm and welcoming environment. The deliberate placement of apertures and vantage points out into the bamboo screen outside the architecture creates visual connections between the indoor environment and nature.

General and Closeup interior views of the Sunnyhills Store in Minami-Aoyama, Tokyo

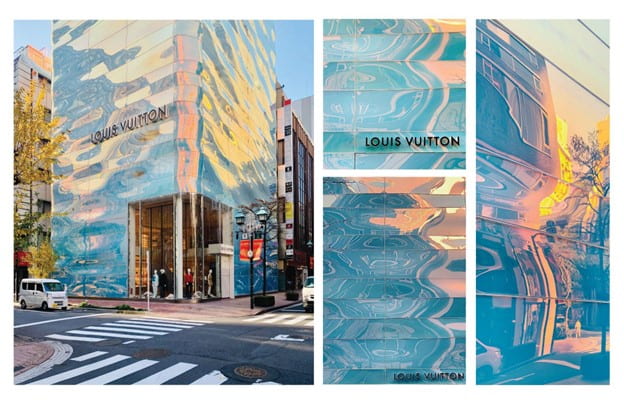

Louis Vuitton Ginza Flagship Store, Jun Aoki & Associates

The Louis Vuitton store at this specific location is designed with an undulating facade that mimics a water ripple effect. The facade utilizes a curved double-glazed system with a dichroic film coating to create the pearlescent effect of water reflection. The concept of the design came from the context of the site which was once on the peninsula of Tokyo Bay. In relation to the concept of the design, the designer also interprets the project as an opportunity to experiment with using water as a material phenomenon. Although it is not currently possible, the effects are very convincing and make for a poetic and playful design.

General and Closeup views of the Louis Vuitton Flagship Store Facade in Ginza, Tokyo

Tokyo Toilet Project

The Tokyo Toilet Project is an initiative promoting public health and wellness in cooperation with the Shibuya government to revamp and redesign public toilets in 17 park locations within the Shibuya district. In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, the restrooms are designed with touchless technology to promote a healthier and cleaner environment for the users of these public facilities. Traditionally, bathrooms are considered private and intimate spaces. Yet, some of the examples of this initiative suggest how bathrooms challenge this notion and connect their users to the outdoor and natural environment.

Nishihara Itchome Park, Takenosuke Sakakura

The 3-stalled public toilet is designed as a gender-neutral facility with amenities and cleaning mechanisms for people of all genders. In front of the stall entrances is a sparse screen of landscaping trees planted to provide an extra layer of privacy. The stalls are built using frosted glass with tree-patterned vinyl adhered to the surfaces for aesthetics and comfort. The shadows cast onto the glass panels by landscape trees outside the bathroom also add to the nature theme. Cleverly, the stall also has built-in voice-activated sensors to play natural white noises in the background for better experience and comfort.

Nishihara Itchome Park Public Toilet

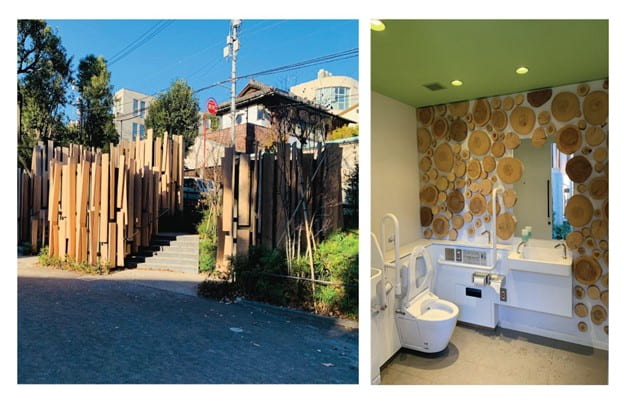

Nabeshima Shoto Park, Kengo Kuma and Associates

The 3-stalled public toilet is designed as a gender-neutral facility with amenities and cleaning mechanisms for people of all genders. The facility is ornamented with wooden slats, with shrubbery and ivies growing on the slats. The door to the bathroom is discreetly placed and inside the stall are tree trunk discs nailed to the wall for aesthetics.

Nabeshima Shoto Park Public Toilet

Haru-no-Ogawa Community Park & Yoyogi Fukamachi Park, Shigeru Ban

These two 3-stalled public toilets are designed as a gender-neutral facility with amenities and cleaning mechanisms for people of all genders. The stalls are built using translucent privacy smart glass which becomes frosted when the door is locked, and transparent when the door is unlocked. The designer’s intention is to create a design that can avoid the awkwardness stemming from people knocking on doors to check for vacancies in public bathrooms. In this case, the facade becomes an indicator of vacancies. The designer has designed two versions of the same toilet in two locations, each with a different color palette.

Conclusion:

The research conducted and the buildings I saw during this trip have taught me the importance of nature in influencing Japanese culture and architectural designs. To the Japanese, nature does not exist as a separate entity from humans. Instead, it revolves around all aspects of life. As architecture is merely a facet of human invention to mimic aspects and moments of natural phenomena, it should fundamentally express its intrinsic connection with nature. The Western idea of “sustainability” does not carry the same weight as it does to Japanese society as the practice of protecting the environment has always been a part of their way of life evident in their mannerisms, social customs, and even designs. As designers and innovators continue to develop novel ways to protect or do less harm to the environment, we should turn to Japanese design philosophies to understand how the world can protect the world more effectively in a systemic manner.