In the beginning was the Word. The APA came later.

The world was not designed to be categorized. When a product engineer wrote the warning material that accompanies the television you just bought–the one that tells you not to plug it into a flooded electrical socket or not to put the plastic packaging over your head or not to eat the packing peanuts–they probably weren’t wondering how that little card could be cited. They just didn’t want you to die and your family sue their company. And the same is true for probably everything that is or has ever been written, recorded, produced, filmed, whatever. It would be nice if things were easy to cite and reference in scholarly writing, but that’s a problem for the people who want to cite things, not the people who make the things being cited.

But maybe you want to cite that little warning card… This leaves you, the citer, in kind of a weird position: what do you do? You’ve googled “APA citation for the little warning card that came with my new television” but all you’re finding is “How to Cite Television Shows.”

Here’s a quick guide for figuring out how to cite any-and-everything. If you want to skip to the examples, go to the bottom.

First, figure out what you have

You won’t be able to cite the thing you want to cite unless you can describe it. Ask yourself these questions (you might not have an answer for everything–that’s fine, just get what you can):

- Does the source have an author? Could be an individual or a group.

- Does the source have a date that it was created? A date that it was updated?

- Does the source seem like something that is liable to change a lot overtime (like a web-page) or something that will probably be stable forever (like a book)?

- Is the source part of some larger source? Is it an article (small) in a journal (big)? An advertisement (small) in a newspaper (big)? A page (small) on a website (big)? A chapter (small) in a book (big)?

- If you had to describe your source in just a few words, what would you say? (i.e. “industry report,” “journal article,” “facebook post,” etc.)

- Is the thing you are citing translated from a different language? Do you know who did the translation?

- What other names accompany the thing you are citing? Is there an editor?

- Does your source have a URL? Could someone else get to that URL, or did you have to sign into some kind of account to get it?

- Has the thing you are citing been published?

Next, find a close match to the thing that you have

Putting together reference entries is a bit like putting together IKEA furniture. You just have to follow the instructions, and occasionally you’ll find yourself with extra pieces after you’re done–you thought those pieces were important, but it turns out they weren’t.

For this part, it would help to have a copy of the APA Publication Manual, 7th Edition. If you don’t, no worries! The APA maintains an online set of examples that is close. Alternately, Purdue’s Online Writing Lab has its own version (which is the exact same thing as the book).

No matter which thing you are using (here I’ll be using the online APA guide) the process is the same.

First, identify which of these categories your source would belong to:

This isn’t cut and dry, but try to use the most narrow definition of your source to pick a bucket. For instance, if the thing you want to cite presumably exists in both textual and online formats (like a government report or journal article) pick the textual format. If it is only available online, choose the online one.

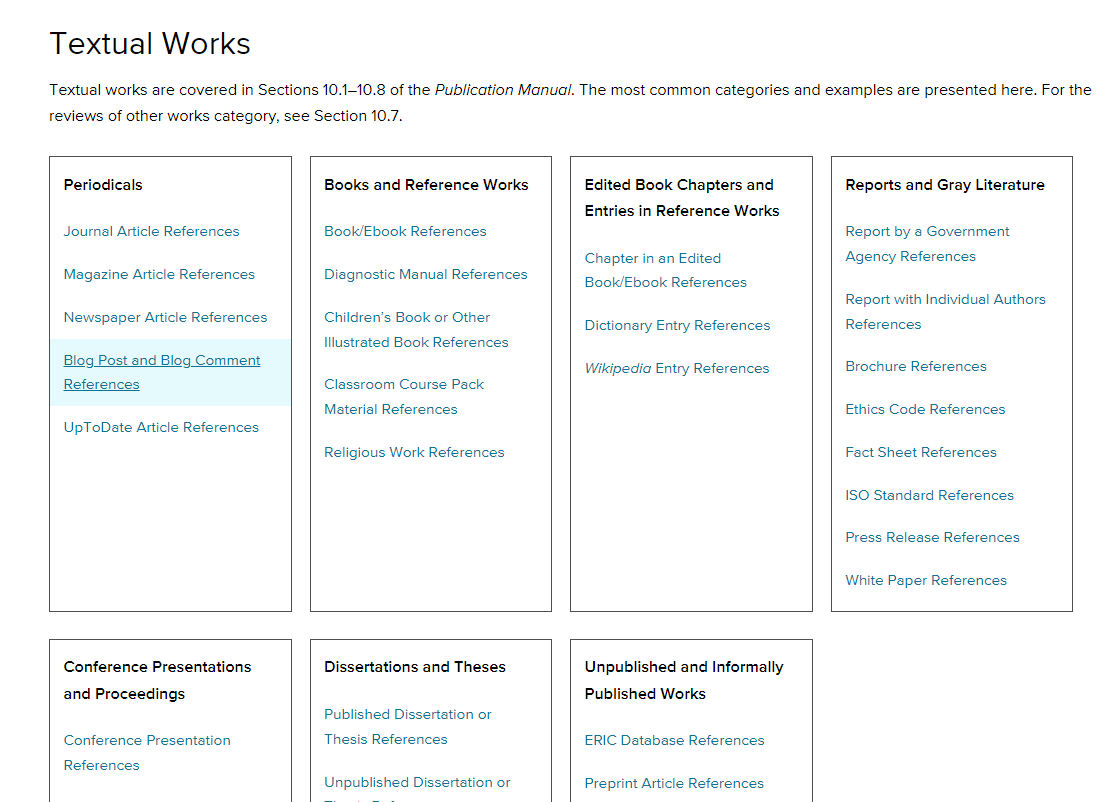

Next, pick which of the materials in that category it most resembles:

It could be that the thing you are trying to cite sort of lands between categories. That’s fine–open both examples in separate tabs.

Lastly, plug in your answers to the questions that we began with to whatever example you’ve chosen:

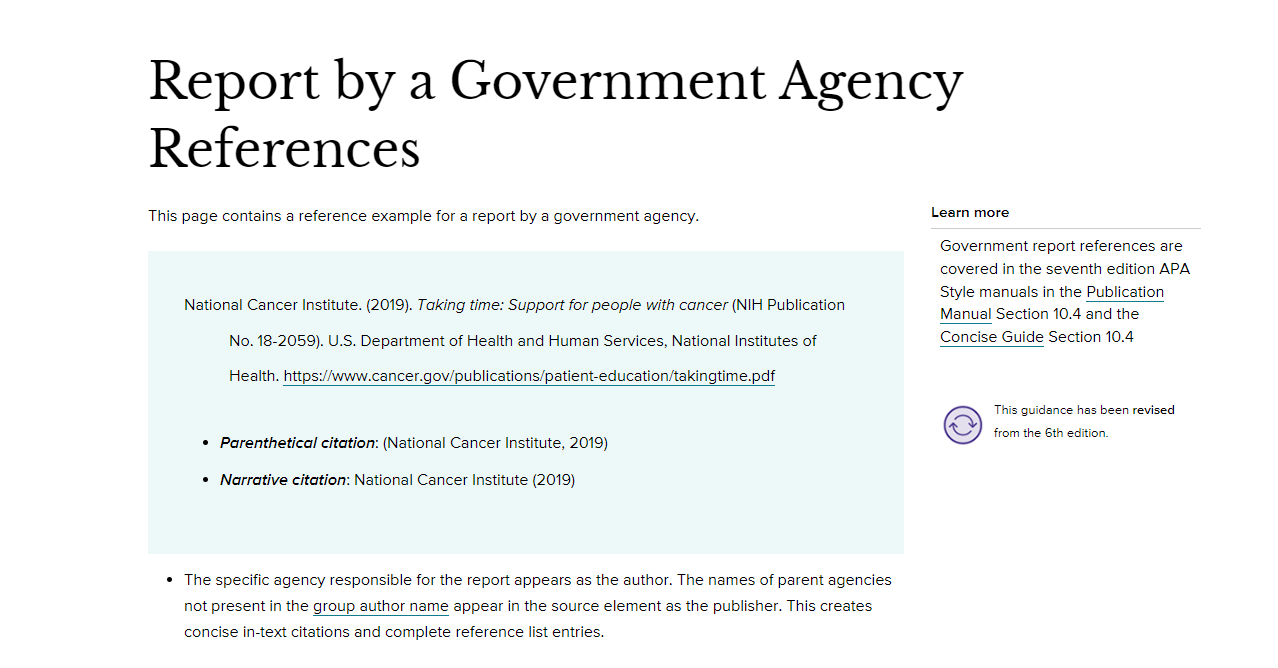

Here I’ve highlighted the “Report by a Government Agency” example because it is actually the same template that lots of different reference entries use. If you’re not sure what you are trying to cite, try to fit it into this format.

Now, the examples on the APA reference site don’t include generalized guides–you’ll have to extrapolate a bit. So, if this is the reference for the example they’ve provided:

National Cancer Institute. (2019). Taking time: Support for people with cancer (NIH Publication No. 18-2059). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/patient-education/takingtime.pdf

Then the generalized form for a report from a government agency would look like this:

Author/Author Organization. (DATE). Title of the report: Italicized in sentence-case capitalization. (REPORT NUMBER). Leading/Publishing Organization in Title Case. URL

You might not have all that information–that’s ok. This is where the artistry of crafting a reference entry comes in. You want to get close enough, but lots of things kind of defy easy citation/reference (like our warning label example).

Once you’ve gotten a draft reference entry down, check for this

First, there are just some mechanical issues to be aware of. APA citations are not all that different than MLA citations or Chicago (author-date) citations, they basically include the same information. What is different, though, is the formatting. Make sure that your reference entry and the example/template all match on the following:

- What is capitalized and what is not

- Punctuation: periods vs commas

- Normal text vs italicized text

- Brackets vs parentheses

- Names: full names vs initials

Besides that, it sometimes helps to consider the purpose of a citation/reference entry pair in your paper. For weird sources, there might not be a generally acceptable way to do things. You might notice certain kinds of sources cited a certain way by some people and differently by others. However, the general point of having references in the first place is somewhat more cut and dry:

- Citations and references have a rhetorical function

- Citations of outside material allow an author to appeal to facts/arguments that are not their own. They can use it to support or contextualize some claim they want to make.

- Citations of outside material allow a reader to justify to themselves that the author’s argument is persuasive.

- Citations and references have an ethical function

- Citations of outside material allow an author to “give credit” to the work of another writer.

- Citations and references have a professional function

- Citations of outside material allow an author to demonstrate the scholarly body of work that they wish to contribute to.

- Citations of outside material allow a reader to find materials that are relevant to a topic of their own interest.

- Citations and references have an instrumental function (especially for students)

- Citations of outside material allow a student to demonstrate that they have done the coursework that professors want them to.

So, to wrap the process up, ask yourself:

- Could someone else find the source I am talking about (or at least know where to find it) by looking at my reference entry?

- Are you giving credit to the people who deserve credit for making it?

- Is there a different way you could have done it? If so, why did you do it the way that you did?

Common & tricky examples

This section will be a work in progress, but there are a few kinds of sources that people get hung up on. I’ll try to update it as I get the notion.

References in APA: Journal Articles

References in APA: Online News Sources

References in APA: Reports (Industry, Government, Company, etc.)