Writing literature reviews is one of the trickiest things you’ll have to do in graduate school. It is even more tricky because a lot of professors will want you to do things that are pedagogically valuable but so tailored to the specific class they are teaching that it can be hard to generalize the lessons you are meant to take away.

This page is meant to be a general overview to the goals and purposes of introductions and literature reviews (or an introduction that contains a literature review–we’ll talk about that), so even if it doesn’t exactly match what you have been asked to do in an assignment, I hope it’ll be helpful.

What is the difference between an introduction and a literature review?

As of writing this, the year is 2022 and words mean nothing. Rather than getting caught up on what these things are in some kind of objective sense, let’s look at what they are supposed to do.

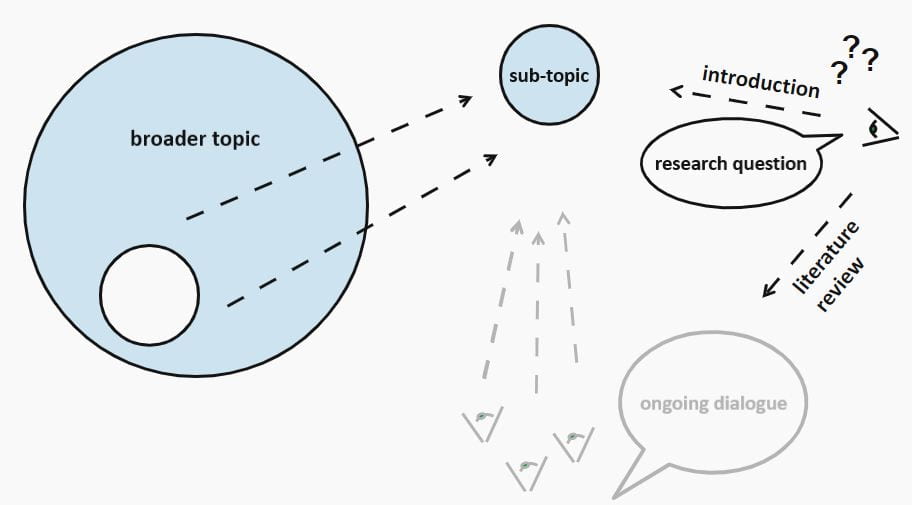

The introduction and the literature review of your paper have the same job. Both are supposed to justify the question(s) you are asking about your topic and to demonstrate to your audience that the thing you are writing about is interesting and of some importance. However, while they have the same job, they do it in two different ways.

An introduction should demonstrate that there is some broader real-world significance to the thing that you are writing about. You can do this by establishing a problem or a puzzle or by giving some background information on your topic to show why it is important. Here’s an example from Brian E. Bride’s “Prevalence of Secondary Traumatic Stress among Social Workers” (2007, link below), where he begins by establishing a problem:

“In the United States, the lifetime prevalence of exposure to traumatic events ranges from 40 percent to 81 percent, with 60.7 percent of men and 51.2 percent of women having been exposed to one or more traumas and 19.7 percent of men and 11.4 percent of women reporting exposure to three or more such events (Breslau, Davis, Peter-son, & Schultz, 1997; Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, & Nelson, 1995; Stein, walker, Hazen, & Forde, 1997). Although exposure to traumatic events is high in the general population, it is even higher in subpopulations to whom social workers are likely to provide services…

Although not exhaustive of the populations with whom social workers practice, these examples illustrate that social workers face a high rate of professional contact with traumatized people. Social workers are increasingly being called on to assist survivors of childhood abuse, domestic violence, violent crime, disasters, and war and terrorism. It has become increasingly apparent that the psychological effects of traumatic events extend beyond those directly affected.”

So, Bride (2007) starts with a broad problem (lots of people with exposure to traumatic events) and narrows it to a more specific problem (social workers who work with those people are exposed to secondary trauma as they assist them).

A literature review should demonstrate that there is some academic significance to the thing you are writing about. You can do this by establishing a scholarly problem (i.e. a “research gap”) and by demonstrating that the state of the existing scholarship on your topic needs to develop in a particular way.

As Bride (2007) transitions to talking about the scholarship on the topic of social workers and secondary trauma, he establishes what scholarship has done and identifies what it has not done.

“Figley (1999) defined secondary traumatic stress as “the natural, consequent behaviors and emotions resulting from knowledge about a traumatizing event experienced by a significant other. It is the stress resulting from helping or wanting to help a traumatized or suffering person” (p. 10). Chrestman (1999) noted that secondary traumatization includes symptoms parallel to those observed in people di-rectly exposed to trauma such as intrusive imagery related to clients’ traumatic disclosures (Courtois, 1988; Danieli, 1988; Herman, 1992; McCann & Pearlman, 1990); avoidant responses (Courtois; Haley, 1974); and physiological arousal (Figley, 1995; McCann & Pearlman, 1990). Thus, STS is a syndrome of symptoms identical to those of PTSD, the characteristic symptoms of which are intrusion, avoidance, and arousal (Figley, 1999)…

Collectively, these studies have provided empirical evidence that individuals who provide services to traumatized populations are at risk of experiencing symptoms of traumatic stress (Bride). However, the extant literature fails to document the prevalence of individual STS symptoms and the extent to which diagnostic criteria for PTSD are met as a result of work with traumatized populations.”

Taken together, Bride (2007) justifies its existence–the research that the author has undertaken in order to read the article that you are now reading–like this:

Broad real world background: Lots of people are suffering from traumatic stress.

Narrowed real world background: People who have suffered traumatic experiences often work with social workers.

Real world problem: Many social workers may through their work suffer from secondary exposure to traumatic experiences.

Broad academic background: There has been a lot of research on secondary traumatic stress

Narrowed academic background: Particularly, this research has shown that social workers are at risk of experiencing symptoms of secondary traumatic stress.

Academic problem/gap: We don’t know how prevalent individual symptoms of secondary traumatic stress are.

Introductions, then, give you space to explain why you are writing about the thing you are writing about, and literature reviews are where you explain what prior scholarship has said about the topic and what the consequences of that prior scholarship are. In an introduction you are writing about the topic; in a literature review you are writing about people writing about the topic.

So does a literature review need to be a separate section from an introduction? Or is a literature review part of an introduction?

It depends on your field, tbh. And on the expectations of the assignment/journal/outlet that you are writing for.

For instance, in the above example (Bride, 2007) the literature review is a part of the introduction. Here’s that paper and some other examples of other places where this is the case. Notice that they do not differentiate between an introductory section and a distinct “Literature Review” as they outline their topic/questions before describing their methodology:

However, plenty of other articles have distinct “Literature Review” sections separate from their introductions. The first two examples name it as such, while the third organizes its literature review with thematic sub-sections:

Whether you separate your literature review into its own distinct section is mostly a function of what you’ve been asked to do (if you are writing for a class) or what the conventions and constraints are of your field.