This is a bit of a walk, but stick with me.

There’s a documentary, This Film is Not Yet Rated, which looks at the MPAA ratings board and the way that filmmakers have to adapt their work to make it through the fairly opaque process of review (at least as of 2006, I don’t know how well it holds up). The documentary has interviews from a bunch of different directors all talking about their experiences trying to edit films according to the feedback that they receive from the MPAA in order to get the rating they want, usually an R (NC-17 is/was a death sentence; again, this is almost 20 years old, streaming might have changed things). The process isn’t transparent, and the filmmakers often have to play a game of “guess what’s in my pocket” with the anonymous review board. Members will say what has lead to a more severe rating (i.e. lots of swearing, sex is too graphic, etc.) but they will rarely offer suggestions about what minimum steps could be taken to guarantee a lesser rating. There’s this weird line being drawn between the MPAA as a group that assigns descriptive ratings and the MPAA as a shadow censorship board.

Anyway, the whole conceit of the film is that the director, Noah Dick, also submits an early cut of this documentary about the ratings board to the ratings board, itself. They give it a pretty severe rating (maybe NC-17?), and the feedback that he receives is troubling. Effectively they say, “There isn’t a particular thing that earns your film this harsh rating–there’s no one thing you could change. The problems are prevalent and diffuse throughout the film.” You could imagine that, faced with the prospect of receiving a rating that would prohibit their film from being shown in theaters or sold by big-box stores, a filmmaker could just take out the offending material. Sure, they might not like it, but you can’t pay your bills with artistic integrity. Problem is, you can’t remove the problem from your work if the problem is everywhere.

Here’s the payoff, thanks for sticking with me:

The same could be said of justifying the significance of your research. Often, students consider the issue of importance/significance/consequence only at the margins of their papers. But this can make the justifications for their work seem thin or inconsequential. And for longer pieces (dissertations), this can become a real problem: You’ve got this multi-chapter, hundred-and-fifty-whatever page project and you get a note from your advisor that just says, “SO WHAT?” The hell do you do with that?

So, here’s a framework for justifying the significance of your work:

There is a lot that we don’t know, so what?

I don’t mean to be diminutive, but I think in framing your research it makes sense to differentiate (real world) problems from academic problems–that is, problems that directly influence or result from the phenomena you are studying and problems with the way that we understand that phenomena. And while I say “problems,” I also mean puzzles. Things that are just uncertain even if you can’t attribute harm to them. I don’t mean “problems” to suggest that the thing you are studying needs to have dire consequences. The way that book clubs contributed to the development of American cosmopolitanism as an identity is a great topic full of puzzling issues (see: Matthew Hedstrom, The Rise of Liberal Religion, 2013). But the significance of those issues is mediated–it matters for the way we understand issues of religious pluralism and identity which also matters for how we reconcile the rise of fundamentalist opposition to those things and so on and so on. I guess I’m trying to walk a tightrope here: just because a problem can be tied to immediate harm doesn’t mean that you don’t have to justify the need to understand that problem; just because a problem doesn’t result in immediate harm doesn’t mean that it isn’t a problem.

Real-world problems are ontological: things about the state of the world or your topic in the world that are troubling or confusing. Academic problems are epistemological: things about our understanding of the state of the world that are troubling or confusing. If you’ve ever seen Margritte’s La Trahison des Images, you’re already familiar with this kind of meta-distinction:

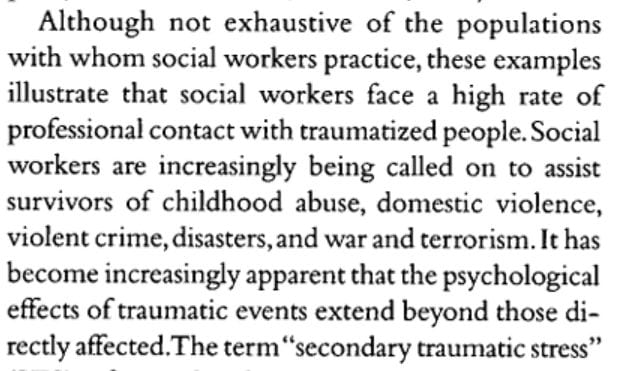

Bride (2007) points out that people suffering from PTSD are also very likely to get support from (or be assigned) social workers. And secondary PTSD is a potential occupational hazard for those social workers. Here’s his statement of the real-world problem:

In short, it is a problem that social workers may suffer from secondary traumatic stress. Here’s his statement about the academic problem:

So, it is a (real world) problem that social workers are at risk of developing secondary traumatic stress and it is an academic problem that we don’t know the prevalence of such cases despite knowing that this risk exists.

In this piece, Wang (2023) offers the academic problem first, and then then clarifies why this is an academic problem (i.e. what real-world puzzle it ties to) later in the piece. Here’s the academic problem:

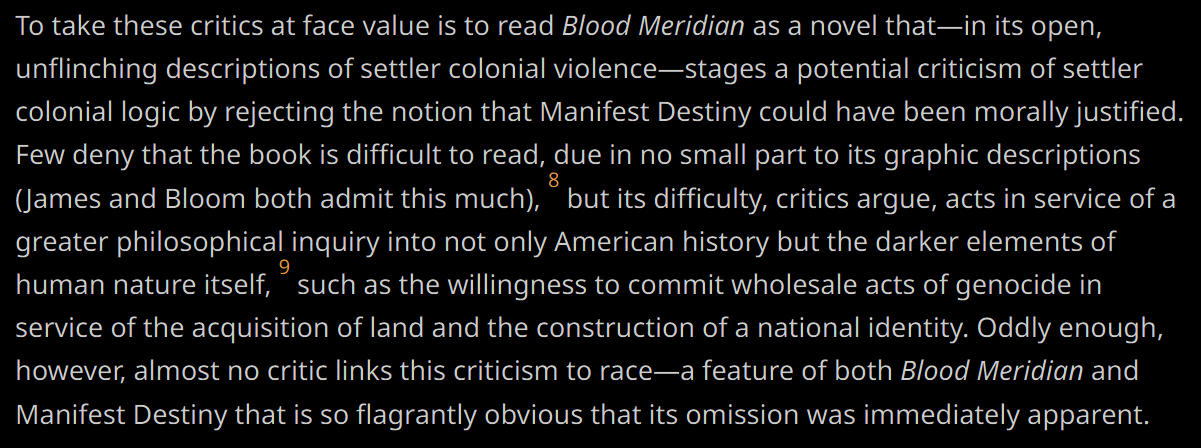

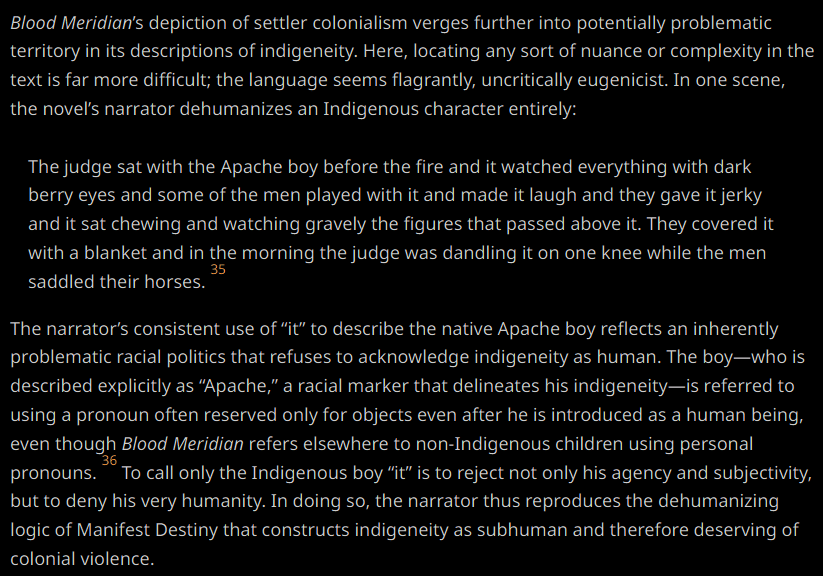

Scholars are brushing aside the issue of race in Blood Meridian, saying that the novel’s violent, racist rhetoric is universal and that it’s done in service to establishing a kind of general descriptive account of the horrors of settler colonialism. However, Wang clarifies later why this is a problem (i.e. what the real world problem is):

Basically, let’s accept that books about racist characters will have a lot of racism in them (in this case a lot of racist violence). Fine. But here, the narrative voice is racist too! Doesn’t that complicate things? It is an academic problem that scholars are willing to view the narrative voice of Blood Meridian as anti-hierarchical because the narration reproduces and reinforces the same kinds of racism as the characters it describes. In other words, if what scholars are saying is true, then the reality of the book that Wang describes is puzzling.

One major difference between these two examples is how, because the problem that Bride (2007) points to is clearly harmful for a group of real people as of its writing (and I imagine into the present), the difference between his (real-world) problem and his academic problem is faint. It is a problem that people are suffering and it is a problem that we don’t know more about how prevalent their suffering is. But Wang’s (2023) piece on McCarthy relies on the real world problem to explain the academic problem and vice versa–both problems reinforce each other.

Compared to the Bride (2007) piece on secondary traumatic stress, the real-world problem described in Wang (2023) is kind of inconsequential–at least in terms of immediate harm. It is a bad thing if social workers suffer, both for themselves and for the people they support. Certainly, it isn’t great if McCarthy’s narrator is a racist (if McCarthy doesn’t frame the narrator’s racism as bad) but… there are lots of racist authors and if an author’s racism removes them from the canon of great literature, oh well. Worse things have happened to better people.

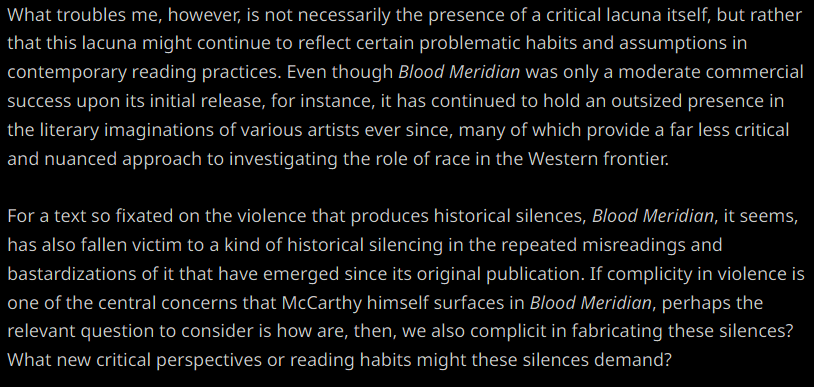

The academic problem for Wang (2023) then is that a real-world problem (the narrator’s racism) is not being properly accounted for by prominent scholarship. And this has broader repercussions:

All together, take from these examples three things:

- The justification of your research should not be an afterthought. Instead, use the framing of a real-world problem and a parallel academic problem to demonstrate the real and scholarly consequence of your work.

- Your work doesn’t need to make the world better. It does, however, need to describe the puzzle that it is trying to understand (real-world problem) and why existing scholarship is not sufficient to understand that puzzle (academic problem).

- If (as in the case of Wang (2023)) the problem you are studying doesn’t hold some kind of ticking-time-bomb-immediate-social-importance, then make sure to demonstrate the consequences of the problem. What happens if this goes unsolved? In that same vein, don’t assume that the consequences of your immediate-real-world problem are apparent to everyone.