Alison Hirsch, PI

|

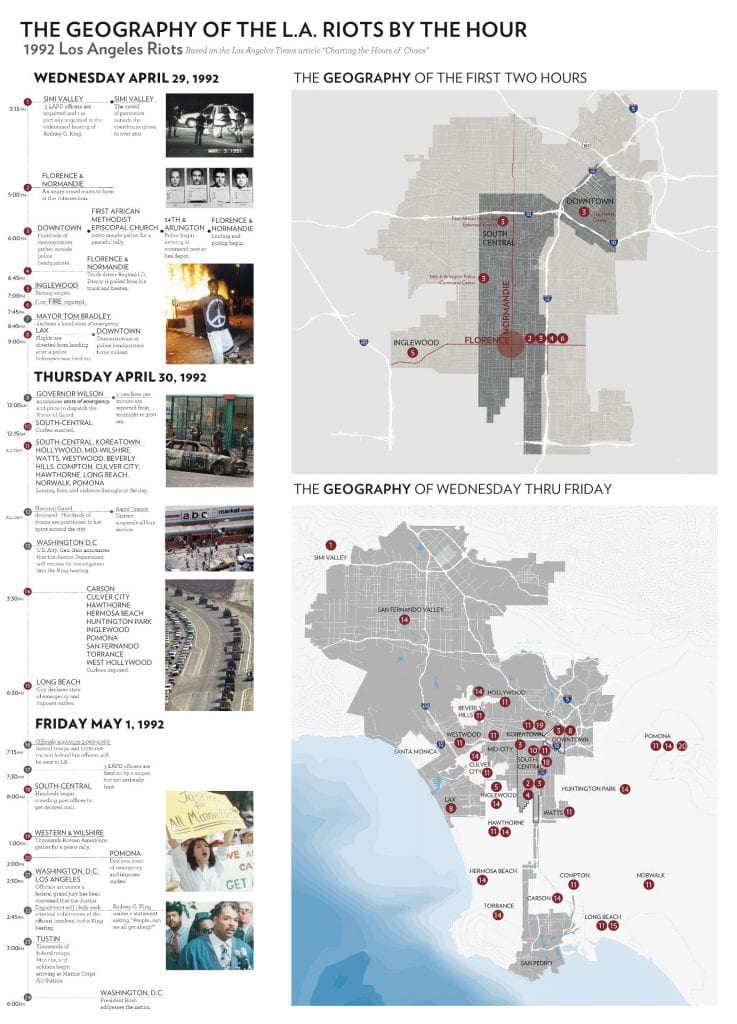

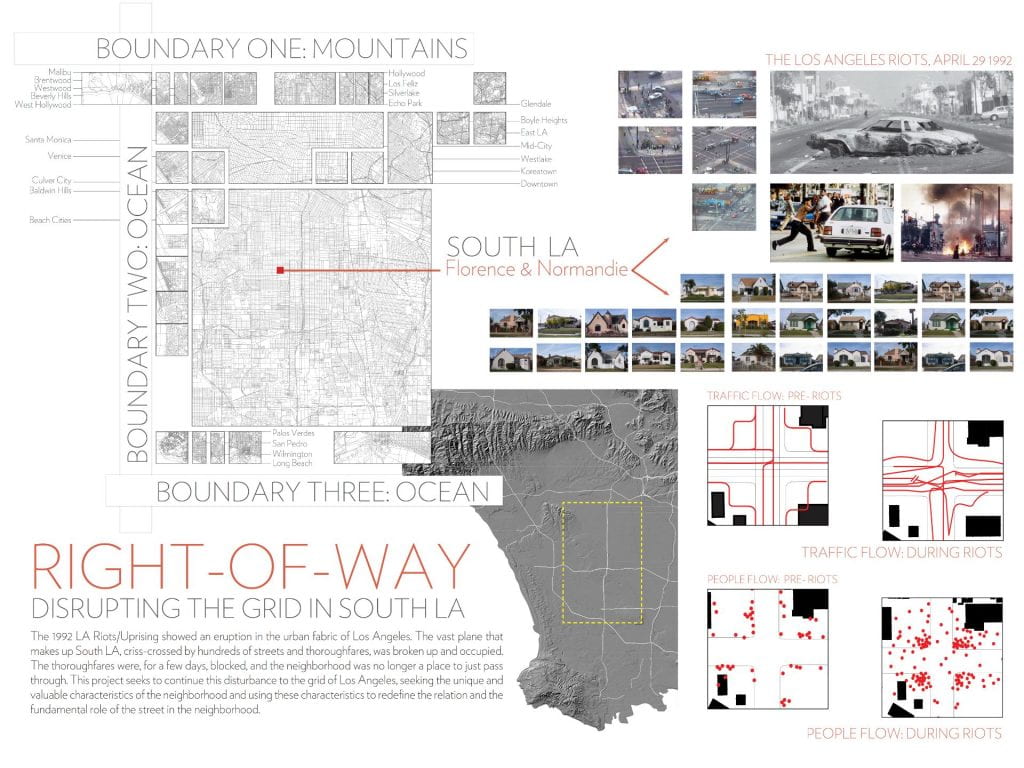

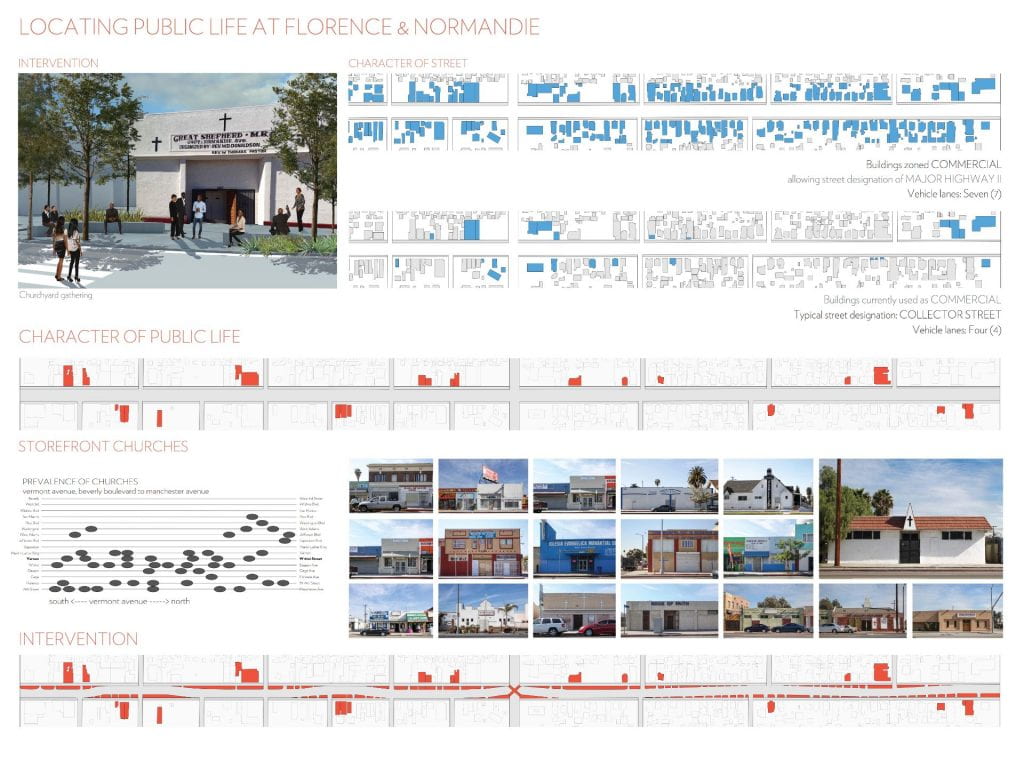

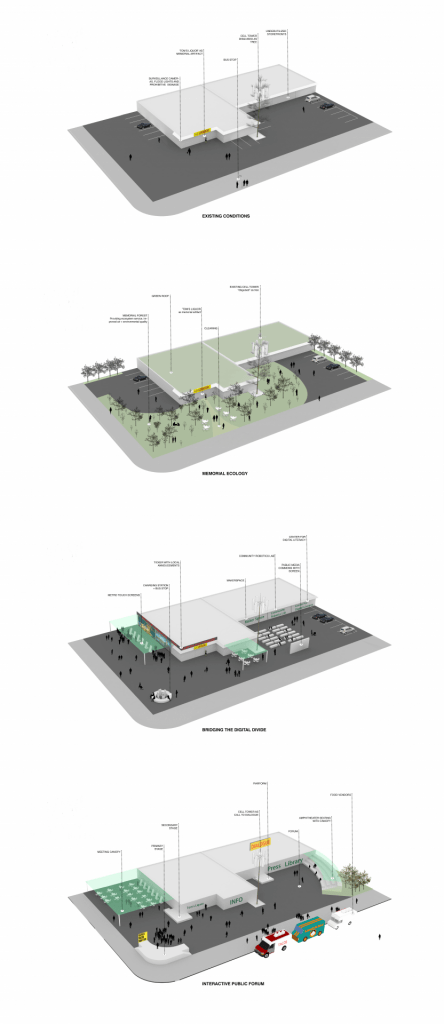

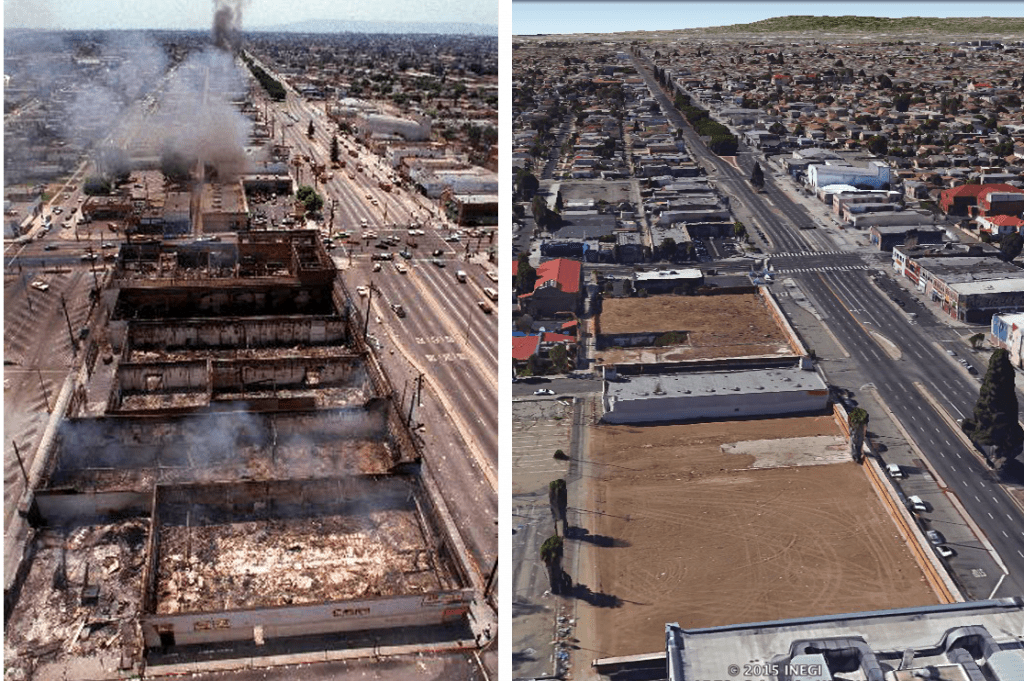

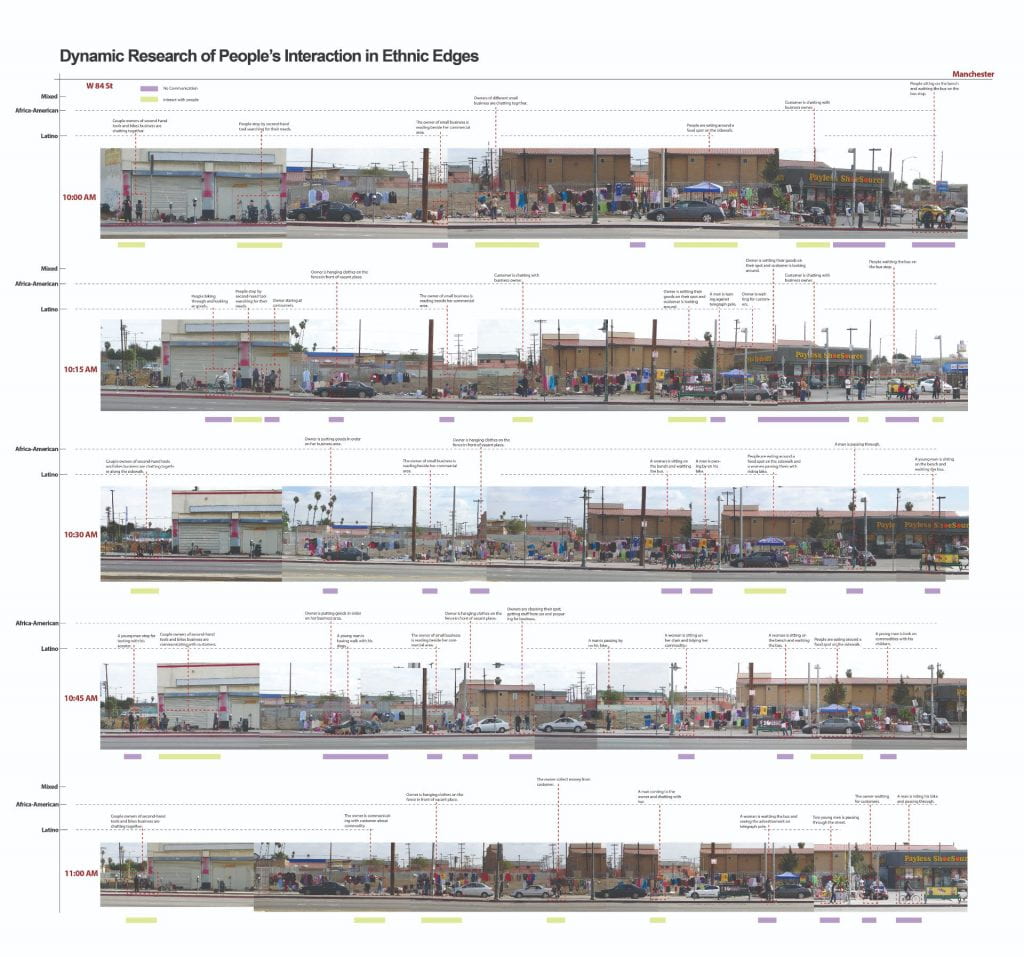

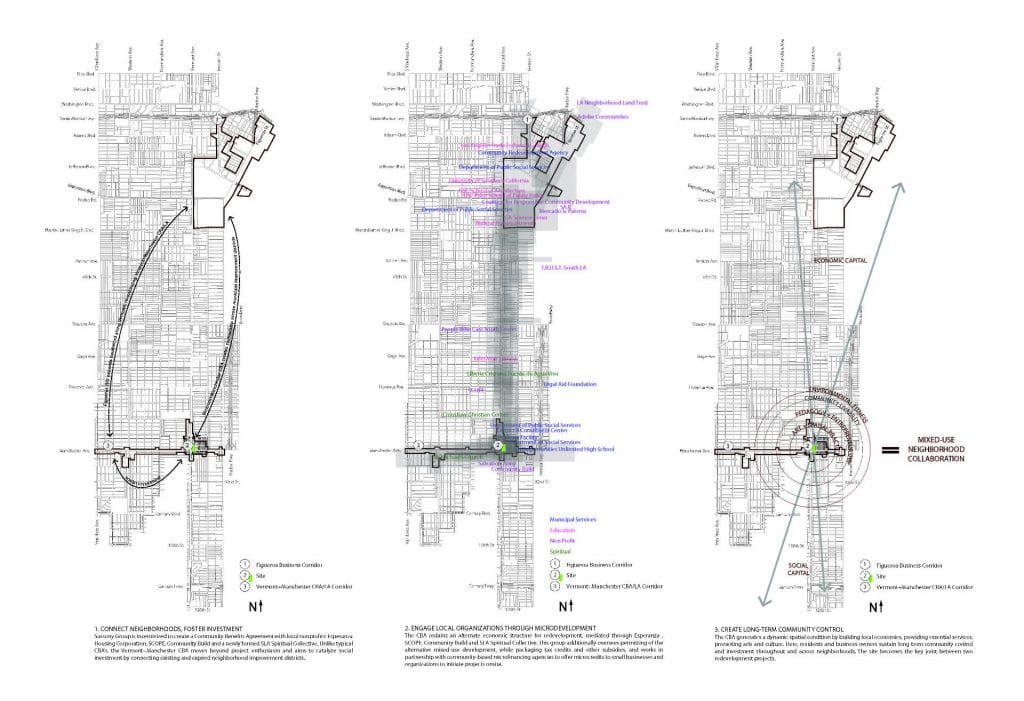

Los Angeles ’92 (2020)This research questions whether and how to physically and fairly recognize histories of resistance to violence and inequality where they occurred. The eight minutes and forty-six seconds caught on video of George Floyd’s killing, under the knee of the Minneapolis police officer outside the corner market on Chicago Avenue and East 38th Street in South Minneapolis was nationally and internationally catalytic. Yet viewing this state-sponsored violence was not unfamiliar to the global public and is a part of everyday existence in communities of color. Video footage of Eric Garner’s killing by police officers in 2014 in Staten Island and Rodney King’s brutal beating by the four white police officers in 1992 in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles presented themselves as visual testimonies to the crimes of the systems in which so many of us are complicit. In a recent widely circulated article, “America’s Cities were Designed to Oppress,” architect and design justice advocate, Bryan Lee responded to this ceaseless cycle, “When it comes to violence against black people in America, history repeats itself so precisely that it can be hard to place any given moment into context.” Thus until we start addressing the realities of our history with truth and reconciliation, it is impossible to move forward. Embedded in this history are both the systems of oppression but also the stories of resistance to those systems – both the individual and everyday, and the moments of rupture when systems have the potential to be overturned or radically transformed. By examining a number of sites most physically impacted by the 1992 Los Angeles Uprisings, this research focuses on the physical formation of the city as an arena for justice and a platform for mobilization emergent from such historically symbolic claims to space and rights. The urban unrest following the Rodney King verdict was a turning point for the city of Los Angeles, which became the physical stage for violent expressions of protest. Specific “flashpoints” triggered increasing unrest with a particular urban geography, yet the most consequential sites exist today without a palpable trace of the events that momentarily brought visibility to long-standing inequities and that indelibly transformed the city. This project considers the potential of reinstating the spatial inheritance of the uprisings as restored sites of resistance and the advancement of collective liberties – with the intention of triggering discourse about the complexities of issues that prompted the uprisings, some of which persist both in Los Angeles and cities across the nation. More generally, it explores how to recognize and confront difficult or conflicted pasts as part of designing the just city, while addressing the urban needs and dreams of today. The fact that many of the sites hardest hit by the riots were the result of looting or arson rather than obvious activism complicates questions, but, as Lynn Mie Itagaki argues in her book, Civil Racism (Univ of Minnesota, 2016, p.19), we might alternatively consider these acts as part of broader political claims on the state. As cultural landscapes, how do we address dire and immediate needs, while asking the public to think critically about their past and future (rather than perpetuate cultural amnesia or appeal to the common insistence on forgetful “healing”)? This may provoke us into awareness to think more critically about the social, cultural, political and economic systems that impact the built world around us, and, in turn, stimulate public discourse, amplify compassion, and mobilize reckoning and paths toward reconciliation. On May 2, 1992, after three days of unrest, thousands of citizens from all over the city armed themselves with brooms and shovels to clean up the charred ruins of South Central Los Angeles. While the urgency of the unrest and violent eruptions of resistance to systems of oppression and their deep legacies could not be swept away by this collective act, the common effort was the first symbolic performance of hope. Yet hope for meaningful change was never fulfilled until perhaps 2020 when demands for change were made not in the neighborhoods still scarred from years of disinvestment and neglect, but organized to move north into the spaces of white wealth and privilege including Beverly Hills, Santa Monica and Hollywood. Instead, in South Los Angeles, residents and organizers held a cleanup as a “peaceful protest” to signal that change can come from within. Three years earlier on April 29, 2017, organizers staged “Future Fest” as a rally, march and arts festival recognizing the 25th-anniversary of the uprisings. These symbolic acts of resistance, hope and change are memorials in and of themselves. Where a just practice of urban and urban landscape design comes in to facilitate these claims to space and rights, expressions of anger and hope, and celebrations of life, culture and love for one’s community is a fundamental question and is part of the path toward restorative justice. This research has been published in the Journal of Architectural Education 72/2 (2018) and as a chapter titled “Reinstating Landscapes of Urban Resistance” in the book Just Urban Design (edited by Kian Goh, Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, Vinit Mukhija; MIT Press, 2022). https://direct.mit.edu/books/oa-edited-volume/5496/Just-Urban-DesignThe-Struggle-for-a-Public-City. |