LJI focuses on communities with histories and threats of dispossession and displacement so questions of place attachment and cultural memory are fundamental to seeking landscape justice. While this emphasis on cultural meaning does not fit neatly into any one of the three priority areas below, it is embedded in landscape thinking and provides a foundation and framework for all three.

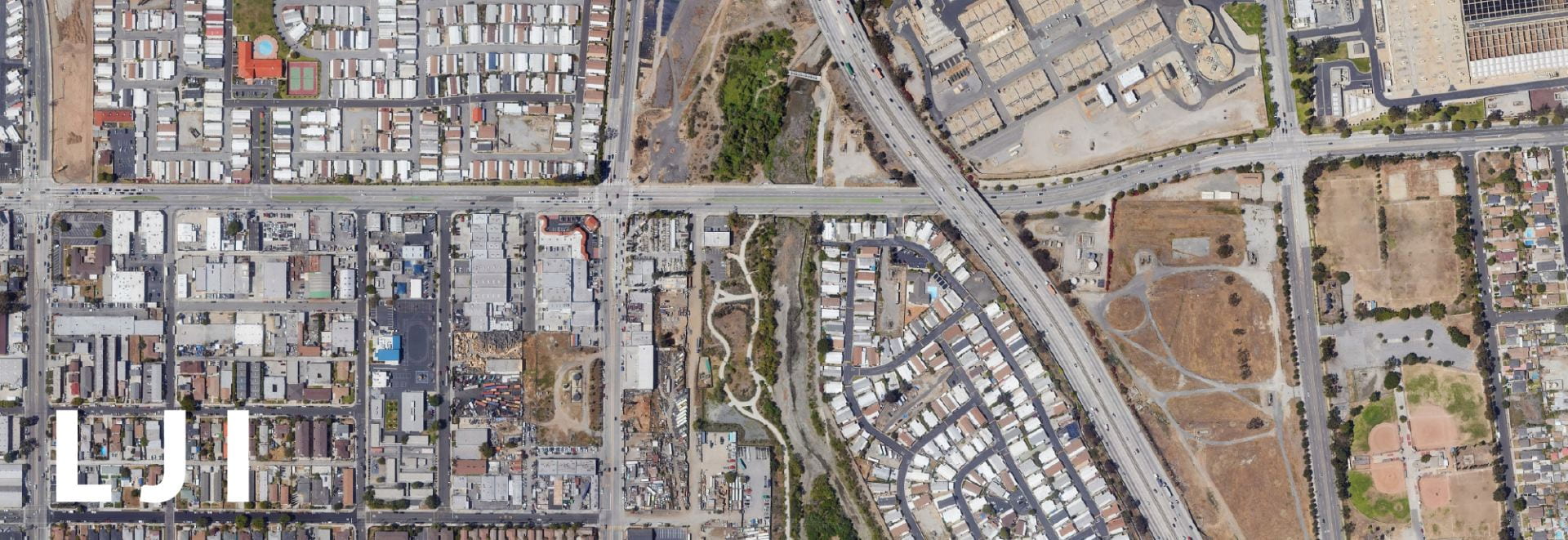

Environmental justice: Efforts in environmental justice focus on the fair or equitable distribution of environmental benefits and burdens. It is too common for low-income communities of color to be disproportionately burdened by industrial pollutants, hazardous wastes, waste disposal and energy production infrastructures, and other incompatible land uses – creating landscapes of toxic accumulation or cumulative risk that lead to poor health outcomes. Seeking a more just environment means not just even distribution of these burdens, but also innovating alternatives to imagine more healthful means of existence. It also means ensuring that there is equitable distribution and access to environmental benefits such as parks, shade, multi-modal streets and multi-benefit infrastructures (etc).

Spatial justice: Spatial justice efforts attempt to confront and reverse the spatial manifestation of racist policies that have historically shaped the urban (and rural) environment leading to segregation, isolation, disinvestment and continued oppression. Spatial justice means the breaking down of those institutions to arrive at more equitable and restorative development policies, as well as more equitable investment in accessible and inclusive public spaces, streets, parks and mobility systems.

Another aspect of Spatial Justice as sought by LJI is related to landscapes of cultural meaning and collective memory in communities whose histories and memories have been overlooked or actively silenced. It relates to how memory and cultural meaning is marked and interpreted in space. Inspired by Dolores Hayden’s Power of Place project in Los Angeles in the 1980s and 1990s, the effort is to understand both the experience of place and the politics of space as integral parts of a cultural landscape.

Climate justice: Seeking climate justice means recognizing the disproportionate impact of climate disruption on the world’s most vulnerable people. It frames climate change not only through the lens of carbon emissions and melting glaciers, but through the framework of civil and human rights. These global movements for climate action are increasingly led by young generations, giving students of landscape architecture – young and old – renewed confidence in the tangible skills they are honing to make meaningful change for the people, species and natural systems experiencing the worst of climate injustice.