Clinical History

- A 69-year-old African male who presented with leg pain, chest pain radiating to the back, and recent significant weight loss.

- CT imaging showed a soft tissue mass anterior to the mid sternum (5.8 cm) and a conglomerate, ill-defined retrosternal soft tissue mass extending to involve the mid to distal sternum (6.9 cm).

- There were also numerous lytic lesions throughout spine , bilateral ribs, and scapulae.

- Imaging also reported suspicion for pathologic fracture with expansile lytic lesions and osseous destruction of multiple ribs. X-ray imaging of pelvis and hip also showed lytic lesions in right femur, left iliac wing, and pubic rami.

- PET imaging mirrored the X-ray and CT imaging findings also highlighting the cardiac involvement.

- Fine needle aspiration was performed on the anterior sternal mass.

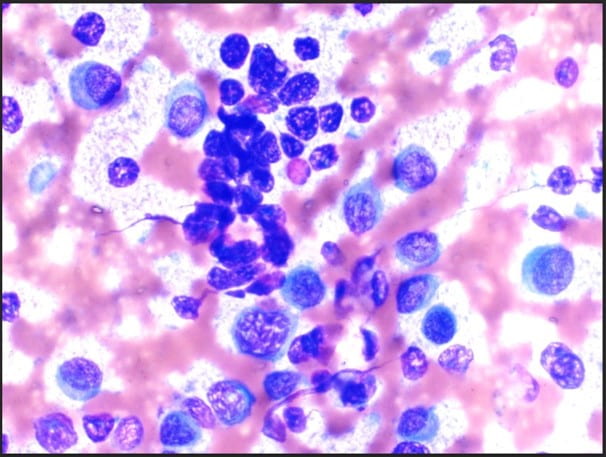

Figure 1. The cellular smear preparation demonstrates singly dispersed and clustered large immature plasma cells with eccentric nuclei, coarse chromatin, prominent eosinophilic nucleoli, high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, and scant to moderate amounts of cytoplasm. Admixed with smaller mature plasma cells and normal blood elements (Diff-Quik, 40X).

Figure 1. The cellular smear preparation demonstrates singly dispersed and clustered large immature plasma cells with eccentric nuclei, coarse chromatin, prominent eosinophilic nucleoli, high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, and scant to moderate amounts of cytoplasm. Admixed with smaller mature plasma cells and normal blood elements (Diff-Quik, 40X).

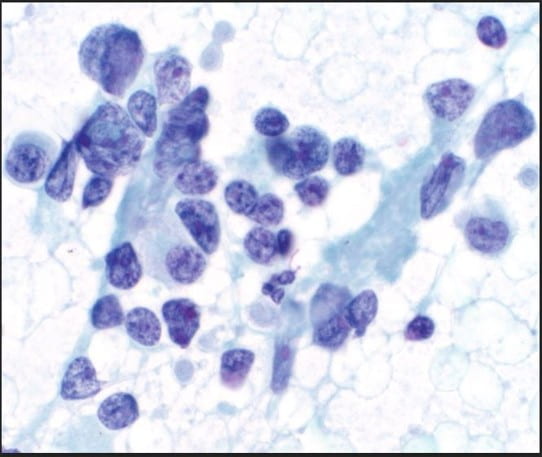

Figure 2. The cellular smear preparation demonstrates mostly clustered immature plasma cells, coarse chromatin, prominent eosinophilic nucleoli, high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, and scant to moderate amounts of cytoplasm. At the periphery of this grouping are smaller mature plasma cells. The Pap stain highlights the prominent eosinophilic nucleoli and the granularity of the coarse chromatin (Pap stain, 40X).

Figure 2. The cellular smear preparation demonstrates mostly clustered immature plasma cells, coarse chromatin, prominent eosinophilic nucleoli, high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, and scant to moderate amounts of cytoplasm. At the periphery of this grouping are smaller mature plasma cells. The Pap stain highlights the prominent eosinophilic nucleoli and the granularity of the coarse chromatin (Pap stain, 40X).

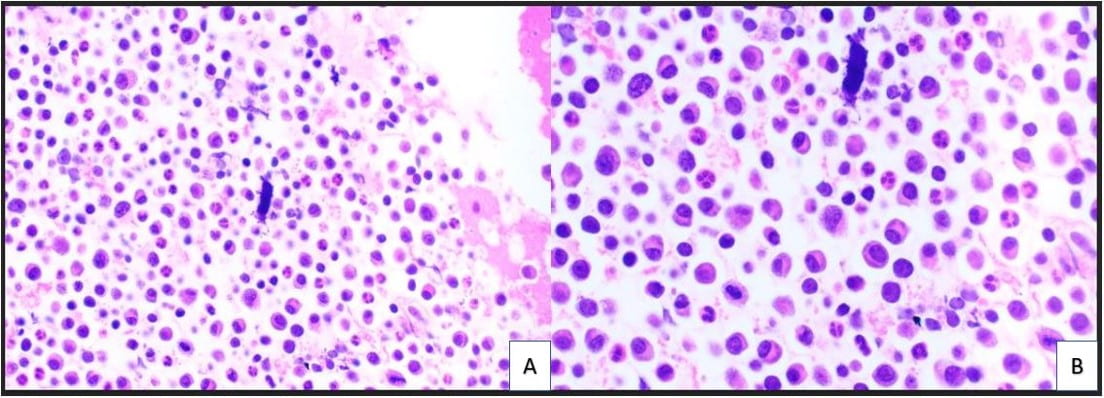

Figure 3. The cell block redemonstrates features seen in the smear preparations with more variably sized plasma cells and blood elements including neutrophils (A: H&E, 10X; B: H&E, 20X).

Figure 3. The cell block redemonstrates features seen in the smear preparations with more variably sized plasma cells and blood elements including neutrophils (A: H&E, 10X; B: H&E, 20X).

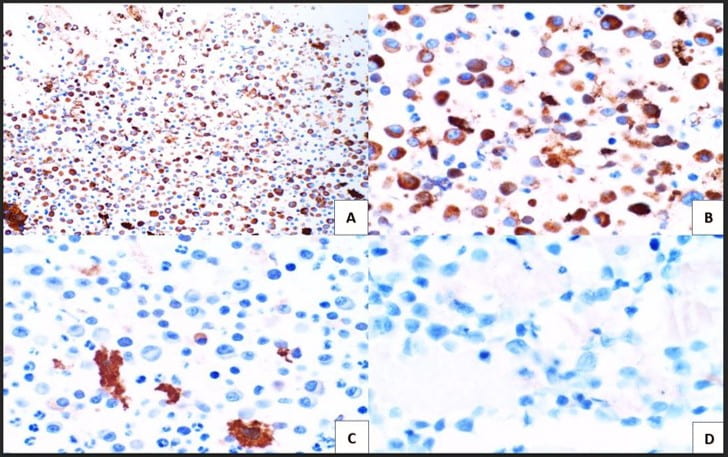

Figure 4. Immunohistochemical studies confirm plasma cell lineage with CD138 (A) strongly positive in both the larger immature and smaller immature plasma cells (10X). Kappa (B) highlights a majority of the plasma cells (20X). While lambda (C) is positive in only a few plasma cells. CD30 (D) is completely negative as is c-Myc (not pictured) (20X).

Figure 4. Immunohistochemical studies confirm plasma cell lineage with CD138 (A) strongly positive in both the larger immature and smaller immature plasma cells (10X). Kappa (B) highlights a majority of the plasma cells (20X). While lambda (C) is positive in only a few plasma cells. CD30 (D) is completely negative as is c-Myc (not pictured) (20X).

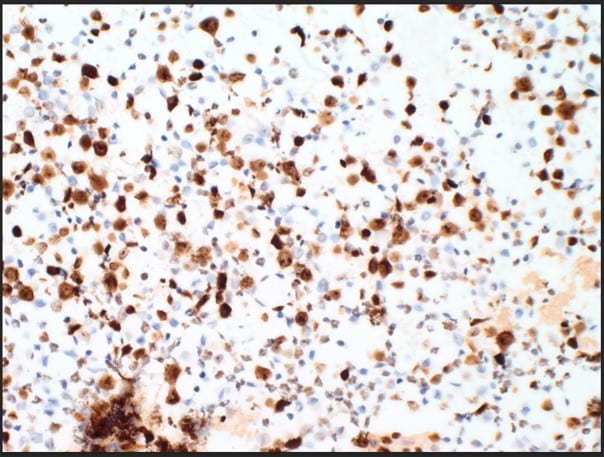

Figure 5. The proliferation rate via Ki-67(MIB-1) within the plasma cells is exceedingly high approximating >80-90% (10X).

Figure 5. The proliferation rate via Ki-67(MIB-1) within the plasma cells is exceedingly high approximating >80-90% (10X).

Discussion

The cytologic features of mostly immature plasma cells (Figures 1-3) as confirmed by ubiquitous CD138 positivity points towards a plasma cell dyscrasia (Figure 4). A high number of the plasma cells show positivity by kappa immunostaining as compared to a significantly lower number of few plasma cells showing positivity by lambda immunostaining; thereby proving kappa restriction (Figure 4). Not pictured in our treatise, but associated with plasma cell dyscrasias, are Russell bodies (hyaline cytoplasmic inclusions containing immunoglobulin) and Dutcher bodies (intranuclear cytoplasmic invaginations). Russell bodies are seen in both benign and malignant plasma cells. Yet, Dutcher bodies are more common in neoplastic plasma cells. CD30 was negative, but expression can be used to decide anti-CD30 targetability in multiple myeloma. c-Myc, which is negative, is assessed as overexpression is associated with adverse clinical outcomes. Ki-67(MIB-1) is high (Figure 5), which is indicative of the aggressive proliferation of the plasma cell neoplasm. Table 1 summarizes interpretation of the immunostains.

The final diagnosis is plasma cell dyscrasia, kappa restricted.

The clinical history combined with the cytology and the histopathology of the follow-up bone marrow biopsy are indicative of an active multiple myeloma.

The bone marrow biopsy was used for further molecular and cytogenetics testing which allowed for stratification of risk, prognosis, and treatment.

Molecular Studies/Cytogenetics

Molecular studies/cytogenetic testing from subsequent bone marrow biopsy of the same site showed the following:

Positive for IGH/FGF3 rearrangement [FISH].

Positive for IGH/CCND1 rearrangement [FISH].

Positive for 1q gain, gain of 9 and 13q deletion/monosomy 13 [FISH].

Negative for TP53 (17p13) deletion, and for rearrangements in IGH/MAF or IGH/MAFB [FISH].

Prognosis

Multiple myeloma has a poor prognosis especially with TP53(17p13) deletion (a high risk chromosomal abnormality). From diagnosis, most patients live from less than 6 months to 10 years with the median survival of 5.5 years. Prognosis is determined by the combination of two risk stratification components: genetics and revised multiple myeloma staging system. The Revised International Staging System (R-ISS) for Multiple Myeloma was devised by the International Myeloma Working group incorporating these two risk stratification components to categorize multiple myeloma patients into three (3) major stages. These were later recommended by NCCN and are standard of practice.

Stage I criteria include (1) beta-2 microglobulin ≤3.5 g/dL and albumin ≥3.5 g/dL, (2) standard risk for chromosomal abnormalities (CA), and (3) normal lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. Stage II is an intermediate category for patients whose clinical and cytogenetic profile are do not meet criteria for either Stage I or Stage III. Stage III criteria include (1) having a beta-2 microglobulin ≥ 5.5 g/dL and (2) being high risk for CA or having a high LDH.

From diagnosis, most patients live from less than 6 months to 10 years with the median survival of 5.5 years. The R-ISS further stratifies this by associating each stage with a specific median progression-free survival (PFS). Patients in Stage I have a median PFS of 66 months. Median PFS for Stage II and Stage III are 42 months and 29 months, respectively. The patient is Stage II based on his beta-2 microglobulin levels and standard/intermediate risk for chromosomal abnormalities.

References

Cibas ES, Ducatman BS. Cytology: Diagnostic Principles and Clinical Correlates. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021.

DeMay RM. The Book of Cells: A Breviary of Cytopathology. American Society of Clinical Pathology: 2016.

Callander NS, Baljevic M, et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Multiple Myeloma, Version 3.2022. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20(1):8-19.

Palumbo A, Avet-Loiseau H, et al. Revised International Staging System for Multiple Myeloma: A Report From International Myeloma Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(26):2863-9.

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Seto M, et al. (eds). WHO classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer: 2017.