64 year-old male with past medical history of meningioma resected in 1998 with recurrence and re-resection in 2006 who presented with a chief of complaint of worsening left sided nasal congestion, difficulty breathing for two weeks and a new right neck mass. Physical exam showed a 4 to 5 cm well-circumscribed mobile, nontender mass in the right lateral neck without overlying skin changes.

Computed Tomography (CT) imaging of the paranasal sinuses was performed and showed a multi-compartmental and transpatial mass. The right maxillary sinus/posterior nasal cavity component measured approximately 5.6 x 5.6 x 3.9 cm, extended across midline, and abutted the left inferior turbinate. The second component centered in the right parapharyngeal, parotid and masticator spaces and measured approximately 5.9 x 3.2 x 2.8 cm. The third largest component was centered in the right parasellar region and extended into the right sphenoid sinus, right cavernous sinus, Meckel cavity and right orbital apex and measured approximately 2.8 x 2.7 x 1.0 cm.

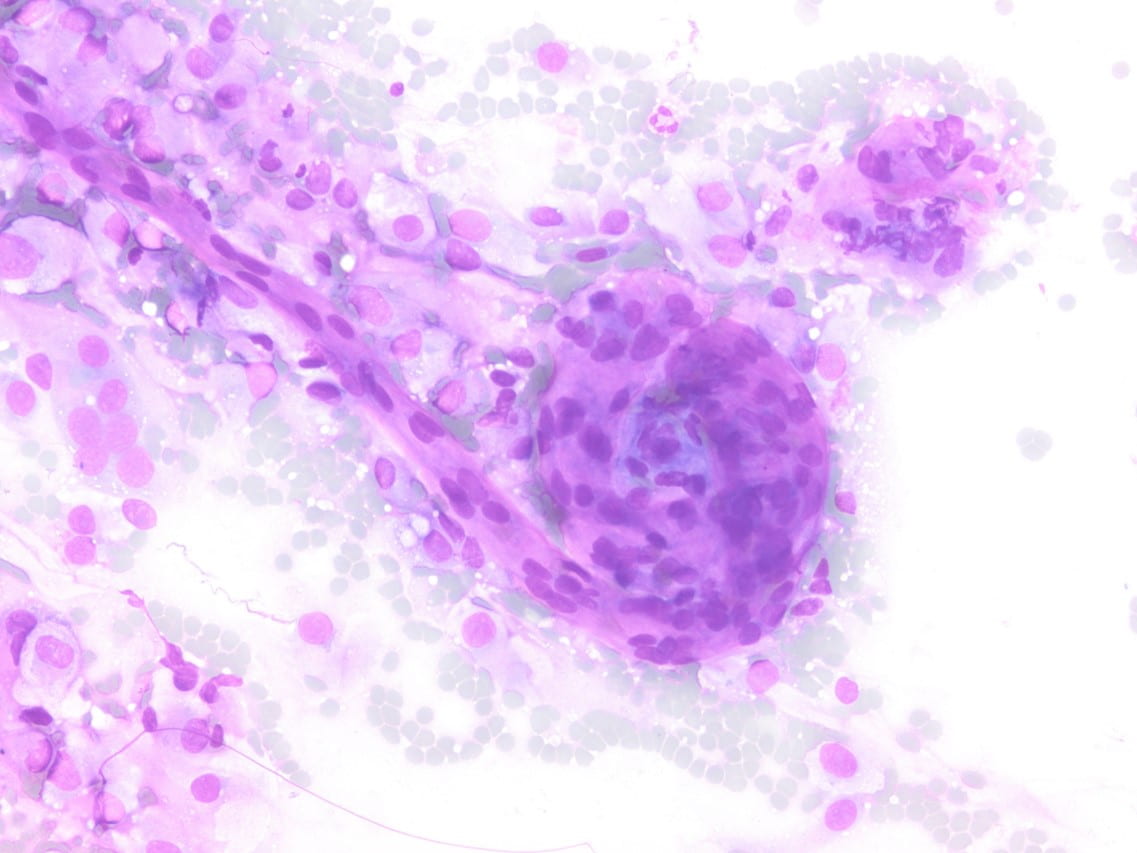

Figure 2. Diff-quick preparation shows whorling architecture (200X).

Figure 2. Diff-quick preparation shows whorling architecture (200X).

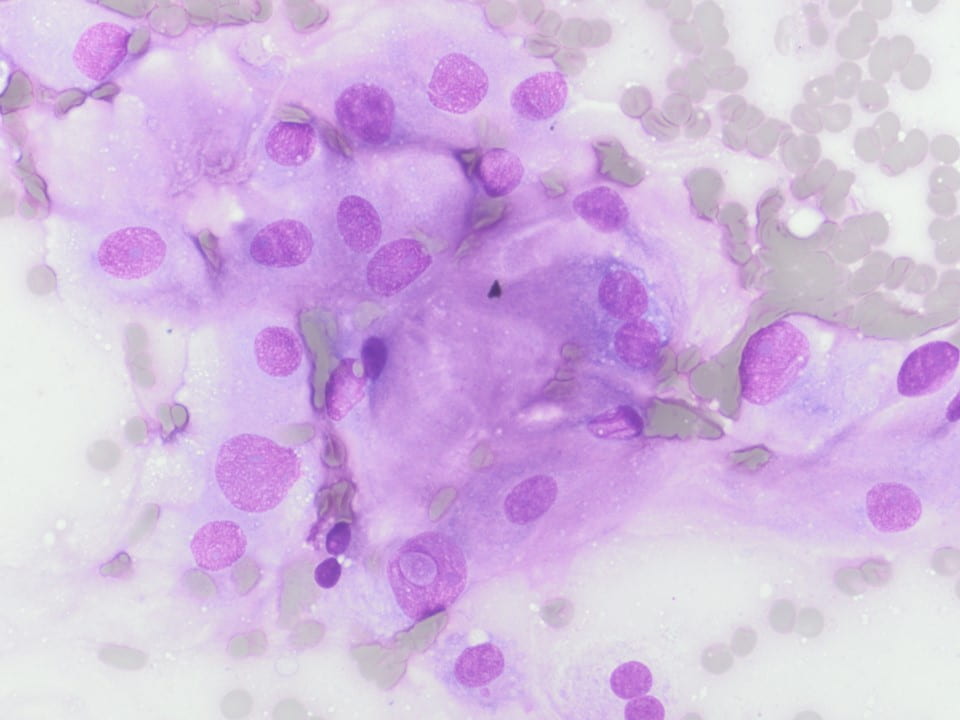

Figure 3. Upon closer inspection, Diff-quick preparations show a) nuclear inclusions (200X) and b) occasional mitotic figures [highlighted by arrow] (200X).

H&E SLIDE:

Figure 4. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain shows a) patternless or sheet-like growth of syncytial cells with areas of increased cellularity (100X) and b) areas of necrosis (200X). High-power views highlight c) prominent nucleoli and a mitotic figure (400X) with d) nuclear inclusions (200X).

ANCILLARY STUDIES:

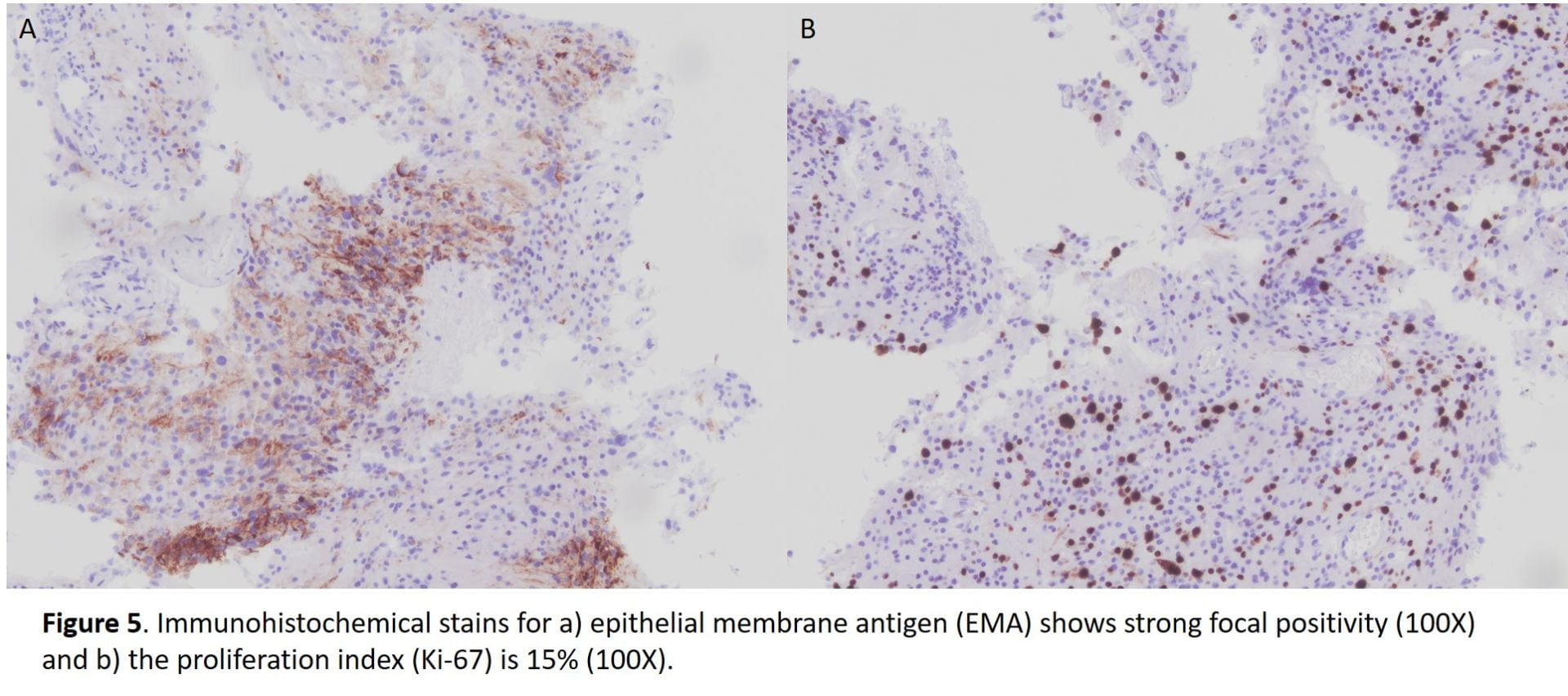

Immunohistochemical stains performed showed the following results:

All immunohistochemical stains performed are summarized in the following table.

Table 1. Summary of immunohistochemical stains.

| Immunostain | Results |

| EMA | Focally positive |

| Progesterone receptor (PR) | Negative |

| CK AE1/AE3 | Negative |

| S100 | Negative |

| Ki-67 | 15% |

DISCUSSION:

Meningiomas are the most common primary central nervous system tumor believed to arise from the arachnoidal (meningothelial cell) [1,2]. They occur in middle-aged to elderly patients with a peak incidence in the sixth decade with a predilection for female gender [1,2]. Although often sporadic, multiple meningiomas can be associated with a hereditary predisposition such as neurofibromatosis type 2 [1,2]. Intracranial meningiomas occur in cerebral convexities and less likely the intraventricular region and orbits [1,2]. Magnetic resonance imaging shows a dural mass with contrast enhancement and characteristic “dural tail” [1,2]. Clinically, they are generally slow growing and benign with neurologic symptoms arising due to compressive behavior; there are infrequent cases of recurrence associated with increased mortality [1,2].

Recurrence is associated with higher histologic grade and extent of surgical excision [1,2,3]. Increasing grade is associated with increased recurrence with a recurrence risk of 50-55% for grade 2 meningiomas [1,2,3]. The WHO 2016 describes 16 histologic subtypes with three grades [1,2,3]. Grade II meningiomas include three different histotypes, i.e. atypical, chordoid and clear cell [2,3]. Histologic criteria for grade II meningiomas includes (1) three or more of minor criteria: increased cellularity, small cells with a high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, prominent nucleoli (readily visible at 10x), uninterrupted patternless or sheet-like growth, and foci of spontaneous or geographic necrosis; or (2) increased mitotic figures, defined as 4 or more mitoses per 10 high-power fields (HPF) or brain invasion [1,2,3]. As in our case, the patient reaches at least three of the minor criteria with increased cellularity, sheet-like growth, prominent nucleoli, and small cell change. The necrosis identified on the case most likely signifies therapy-related changes. Mitotic figures although observed in our case do not reach the 4 mitotic figure per 10 hpf threshold, possibly due to insufficient sampling of the tumor.

Cytologic features of meningiomas include syncytial clusters of spindled cells arranged in lobules with chromatin clearing and wispy cytoplasm [1,4]. Cells may be arranged in “whorls” that are characteristic of a meningioma, albeit typically low-grade [1,4]. Psammoma bodies and nuclear pseudoinclusions may be seen [4]. Abundant bright eosinophilic psammoma bodies may be seen in secretory meningioma [4]. Degenerative changes may be associated with cells with atypical nuclei with smudgy chromatin and abundant cytoplasm [4]. Atypical meningiomas are associated with increased cellularity and sheet-like growth, as observed with our case [1,4,5]. If there is an abundant necrotic background, one should consider preoperative embolization therapy or other etiologies such as metastatic carcinoma [4]. On H&E, meningiomas show similar features to cytology such as syncytial cells with whorling architecture and clear chromatin patterns; psammoma bodies and nuclear inclusions may be present. A differential diagnosis may include metastatic carcinoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and hemangiopericytomas; all which lack the characteristic whorls or delicate cytoplasm seen in meningiomas [4].

Meningiomas show positive immunohistochemistry for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA); a more recent immunostain, somatostatin receptor 2A (SST2A), has also shown to be positivity in recent studies [6]. 70-80% of meningiomas are also positive for progesterone receptor and lesser immunostaining with estrogen receptor [7,8]. In some studies, male gender, as observe in our case, serves as a negative prognostic factor and a correlation between meningiomas that are less likely to stain for progesterone receptor are associated with malignant meningioma [2,3,5]. This progesterone receptor-negative immunophenotype is seen in our case. A Ki-67 proliferation index over 4%, also observed in our case, has also been correlated with increased recurrence risk, but is most commonly used as an adjunct to standard WHO grading and not as an independent factor [1,2].

Additionally, brain invasion and a mitotic rate have been shown to be the most important prognostic indicators of recurrence in meningiomas, especially after gross total resection [3,5]. Minor criteria of hypercellularity, sheeting, macronucleoli, and small cell change is associated with decreased progression free survival [5].

Awareness of this common central nervous system tumor and its histologic grading, specifically in the context of cytopathology, is of utmost importance for all pathologists.

REFERENCES:

- Perry A, Louis DN, Budka H et al (2016) Meningiomas. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Ellison DW, Figarella- Branger D, Perry A, Refeinberger G, von Deimling A (eds) WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. IARC press, Lyon, pp 232–245.

- Buerki RA, Horbinski CM, Kruser T, Horowitz PM, James CD, Lukas RV. An overview of meningiomas. Future Oncol. 2018;14(21):2161-2177.

- Barresi V, Lionti S, Caliri S, Caffo M. Histopathological features to define atypical meningioma: What does really matter for prognosis? Brain Tumor Pathol. 2018;35(3):168-180.

- Field, AS and Zarka, MA. Practical cytopathology: A diagnostic approach to fine needle aspiration biopsy. Elsevier; 2017: 483-533.

- Perry, Arie, Stafford, Scott, Scheithauer, Bernd, Suman, Vera, Lohse, Christine. Meningioma Grading: An Analysis of Histologic Parameters. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21(12):1455-1465.

- Menke JR, Raleigh DR, Gown AM, Thomas S, Perry A, Tihan T. Somatostatin receptor 2a is a more sensitive diagnostic marker of meningioma than epithelial membrane antigen. Acta Neuropathologica 130(3), 441–443 (2015).

- Hsu DW, Efird JT, Hedley-Whyte ET. Progesterone and estrogen receptors in meningiomas: prognostic considerations. Neurosurg. 86(1), 113–120 (1997).

- Pravdenkova S, Al-Mefty O, Sawyer J, Husain M. Progesterone and estrogen receptors: opposing prognostic indicators in meningiomas. Neurosurg. 105(2), 163–173 (2006).